by Anthony G. Williams

World War 1

At the Olympia Aero Show in London in early 1913, at least two aircraft were on display that were armed with machine guns. One, designed by Vickers at the behest of the Admiralty and informally known as the Destroyer, carried a Vickers .303 machine gun; the other, designed by Claude Grahame-White, had a Colt-Browning model 1895 installed in the nose. Both were pusher designs carrying their guns on movable nose mounts. The Vickers design was the ancestor of the FB.5 “Gun Bus”, which entered service in November 1914, then armed with a Lewis gun.

But the aircraft in service at the start of the Great War were unarmed, and their initial use was for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. Airmen soon began to carry aloft pistols, revolvers, shotguns, rifles or carbines to take pot-shots at the opposition. A machine gun was a much better weapon for shooting at other aircraft, but the .303 inch Vickers was water-cooled and weighed some 40 lbs. Fortunately, BSA had acquired a licence to manufacture the American Lewis Gun. This was lighter at around 26 lbs, and its ammunition was held in a pan magazine clipped to the gun, instead of the rather cumbersome fabric belt of the Vickers. The air-cooled barrel was within a bulky sleeve that covered light-alloy cooling fins, but as the motion of the aircraft provided adequate cooling air, most of this arrangement was soon stripped away. This, in conjunction with removing the stock, reduced the weight to about 17 lbs.

The Mk II version, used later by the RFC, had a smaller sleeve fitted to protect the mechanism, but the final Mk.III version reverted to a stripped barrel. Other changes during the war increased the capacity of the magazine from 47 to 97 rounds and increased the rate of fire from around 550 to between 700 and 750 rounds per minute (rpm). The Lewis was well suited to flexible mountings designed to allow a gunner to move the gun around to point it in different directions, such as the Scarff ring.

But the most effective offensive armament was a fixed, forward-firing machine gun. “Pusher” designs with the engine and propeller behind the crew allowed for the gun to be installed forward in the nacelle, and they were used until 1917, but they were at a performance disadvantage. “Tractor” designs with the engine and propeller in front were aerodynamically superior but the installation of a forward-firing gun was challenging. Early attempts to mount a gun to fire at an angle past the propeller were less than successful. In April 1915 the French pilot Roland Garros (after whom the French Open tennis competition is named) equipped his Morane-Saulnier L with a forward-firing machine gun and steel deflector plates fitted to the propeller, which at least reduced the risk that bullets would damage the propeller. In September 1915 the RFC placed an order for a small number of similarly equipped Morane-Saulnier Type N aircraft, which were fitted with Lewis or Vickers machine guns.

The first satisfactory solution for biplane fighters was to mount the gun on the top wing, so that the bullets would miss the propeller. With early mountings of this type the gun was fixed in place, which meant that the pilot had to stand up to change the magazine. Eventually, the Foster mounting was developed, which allowed the pilot to pull the gun down towards the cockpit for magazine changes, and incidentally permitted the gun to be fired upwards.

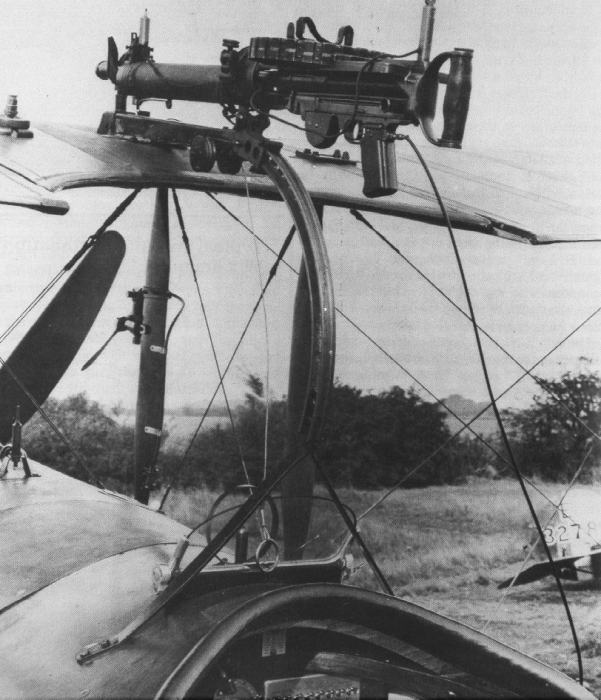

Foster mounting for a Lewis Mk II on an Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a

The Germans were the first to adopt a more sophisticated solution (first proposed before the war) of timing the shots from the machine gun so that they would pass between the propeller blades. These synchronisation systems involved converting the gun so that it could fire single shots each time the firing line was clear.

The Vickers was far more suitable for synchronisation than the Lewis, because the Vickers fired from a closed bolt and the Lewis from an open bolt. When the Vickers was ready to fire there was a round in the chamber, the action was locked and only the firing pin needed to be released. Between 1/180 and 1/200 of a second later, the bullet would fly past the propeller. In that time, critically depending on engine revolutions, the propeller might rotate anywhere between 15 and 60 degrees, but that left a large enough safety margin with a two-bladed propeller. In the Lewis the bolt was held back and the chamber empty, so each time the firing signal was sent, there was a longer delay while the bolt started to move forwards, collected a cartridge from the magazine, loaded it into the chamber, locked the breech and then fired. Despite many attempts to modify the Lewis, this took too long for safe firing.

By then, the planes were powerful enough to cope with the extra weight of one and later two Vickers guns. They were usually mounted on top of the engine, with the breech extending into the cockpit so that the pilot could clear jams. The Vickers was modified first by emptying its water jacket and punching holes in it to let cooling air through, reducing the weight to around 28 lbs, and subsequently by providing it with a slimmer jacket, although this Mk.III version wasn’t adopted until after the War. Its free rate of fire was also increased from 550 to 850 rpm by fitting a Hazleton muzzle adaptor, although the actual RoF of a synchronised gun would have been much less than this, and dependent on engine revs.

I now want to turn to ammunition developments, since aerial fighting in the Great War prompted considerable development efforts, in two directions. One was to improve the quality of the ammunition. A certain percentage of stoppages was acceptable in a ground gun, since the gunners could usually quickly clear the jam, but it was a different matter in an aircraft. In an attempt to resolve this, the British introduced in 1917 “Green Label” (or “Green Cross”) .303″ ammunition specifically for synchronised guns. This was taken from standard production lines, but carefully selected from batches which complied with tighter manufacturing tolerances. This was followed up in 1918 by establishing special production lines to make high quality ammunition. This was known as “Red Label”, or “Special for RAF, Red Label”, “Special for RAF” and finally “Special”.

The second line of development was the production of a variety of specialist bullets, initially prompted by the need to destroy hydrogen-filled spotting balloons and airships which were little affected by having small holes drilled through them. The gas was flammable, but would only burn when mixed with air. Several attempts were made to devise bullets filled with explosive and/or incendiary chemicals. Initial work was in larger-calibre guns simply because the bullets were bigger, but this was soon replaced by .303″ ammunition. Some types of incendiary, such as the Buckingham which contained a phosphorous/aluminium mixture, were ignited on firing and burned slowly throughout their flight leaving a smoke trail, while others ignited on impact. The Pomeroy or PSA explosive bullet contained nitro-glycerine and was purely explosive, but the Brock, which contained potassium chlorate, and the RTS (Richard Threlfall and Sons) with both nitro-glycerine and phosphorous, had both explosive and incendiary effects, so were known as HEI bullets. Note in the photo below that the first three rounds were loaded with Cordite propellant (so-called because it was extruded into cords), the last with nitro powder. Use of these bullets was initially somewhat hazardous as the early versions had a reputation for premature detonations, and elaborate handling precautions were required. Also, because they could “cook off” in the hot chamber of the Vickers, it was safer to use them in the Lewis, which was thus often retained by home defence fighters.

.303 rounds sectioned: Brock incendiary, PSA Mk I HE, PSA Mk II HE, RTS Mk II HEI (Peter Labbett)

The Interwar Period

By the end of the Great War the Vickers and Lewis guns in .303″ calibre were the established RAF armament and remained so until the late 1930s. They were also widely sold abroad, including to Japan, which was still using them at the start of World War 2. There was little money to buy armaments after the end of the Great War, but that didn’t stop theorising and experimentation, particularly in investigating the potential of larger-calibre guns.

Three different classes of aircraft gun began to emerge in various nations: improved rifle calibre machine guns, heavy machine guns, and automatic cannon. Rifle calibre guns were those which use the same ammunition as the standard military rifle, firing bullets of around .30-.32 inch in diameter (7.5-8 mm calibre). Heavy machine guns fired much bigger cartridges with bullets of around .50-.60 inch diameter (12.7-15 mm) which were three to six times as powerful as rifle-calibre ammunition. Cannon fired projectiles of 0.8 inch (20 mm) or greater diameter, which was generally considered to be the smallest worthwhile size to use high-explosive ammunition.

Vickers developed a scaled-up version of their .303″ MG, chambered for a new .5″ (12.7 mm) cartridge. This was tested by the RAF in the mid-1920s against the new .50″ Browning heavy machine gun, which was more powerful. The conclusion was that neither offered sufficient advantages to replace .303″ MGs, since the slightly bigger hole they could punch wasn’t adequate compensation for their greater size and weight and their lower rates of fire. The Swiss Oerlikon 20 mm cannon, developed from the German Becker of the Great War, was also tested in the late 1920s and early 30s and proved more promising since its explosive shells could do a lot more damage than just punching bigger holes, but it was big, heavy and slow-firing. The RAF decided in the mid-1930s to stick with the .303″ calibre for the time being, while noting that a 20 mm gun would be the preferred replacement if armour protection were applied to warplanes.

After competitive tests, two new machine guns were selected: the US Browning and the Vickers Gas Operated (known also as the VGO or Class K), a modification of the Vickers-Berthier light MG. The Browning was considerably modified over the American original. It was not just converted from .30 to .303 inch calibre but also modified to fire from an open rather than a closed bolt. The Browning was belt-fed and initially intended for fixed fighter installations (although later adapted for use in turrets). In contrast the VGO used a pan magazine of 100 rounds and was for flexible mounting.

The rifle-calibre guns used by different air forces were quite similar in performance, but there was more variation in the characteristics of heavy machine guns, with weights ranging from 40 to 90 lbs and rates of fire generally between 700 and 900 rpm. There was an even greater variation in size and power among the 20 mm weapons (let alone the few even larger-calibre cannon), with weights from 50 to 120 lbs, rates of fire from 400 to 800 rpm, and considerable variation in muzzle velocities, which affected their hit probability. The photo below indicates how the ammunition differs in size and power, with three famous cartridges used by the RAF during World War 2 compared with Luftwaffe ammunition in the same classes. The considerable power of the Hispano is obvious.

The three standard WW2 RAF rounds: .303″, .50″ and 20 mm Hispano (left), compared with representative German ammunition: 7.92 mm, 13 mm MG 131, 15 mm MG 151, 20 mm (MG-FF) and 20mm MG 151/20

World War II

In 1931 the RAF had issued a fighter specification F.7/30 that increased the number of guns on a fighter from two to four. In 1934 the Air Ministry accepted the advice of the Operational Requirements Branch that a six or preferably eight-gun battery should be installed in fighters, reasoning that gun firing opportunities would be brief due to the increasing speeds of aircraft. This was incorporated in specification F.5/34, which would however be superseded by the development of the Hurricane and Spitfire with similar armament.

Work was also done on improved .303″ ammunition. The steel-cored armour-piercing and Buckingham incendiary/tracer (designated B.Mk IV) rounds were based on old designs, but a new incendiary, the B.Mk VI, was developed by Major Dixon, loosely based on the Belgian De Wilde design. In the picture below you can see the steel core for the AP bullet and the construction of the famous B Mk VI incendiary.

Sectioned .303″ rounds, from the left: tracer, armour-piercing and B Mk VI incendiary (Dixon/De Wilde)

In firing tests, the B. Mk VI had a 20% success rate in setting fuel tanks alight, twice that of the Buckingham or the equivalent German 7.92 mm round, and also had the happy side-benefit that the flash of ignition on impact told the pilot that he was on target. The Dixon ammunition was first issued in June 1940 and was at first in short supply. The RAF initially set up its eight-gun fighters with one gun firing Dixon incendiary, two guns with Buckingham incendiary/tracers, two guns with armour-piercing and three guns with “ball” rounds with lead cores. By 1942 the standard loading for fixed guns was half with AP and half with incendiaries.

As a result of early battle experience, aircraft armour and self-sealing fuel tanks were rapidly applied, and the .303 guns lost effectiveness. Some improvement was achieved by reducing the gun harmonisation range from 400 to 250 yards in order to concentrate the firepower of the RAF’s fighters, but it was clear that a more powerful gun was needed. This eventually arrived, just too late for the Battle, in the form of the 20 mm Hispano.

The Hispano-Suiza HS 404 was developed at the French arm of the European Hispano-Suiza company in the mid-1930s to be superior to the Oerlikon FF S, which the French built under license as the HS.7 and HS.9. The demonstration of a prototype to British officers in Paris in 1935 was convincing, but the processes of obtaining approval to buy the gun, setting up a subsidiary Hispano factory at Grantham (BMARCO), redrawing the gun to imperial rather than metric units, testing the prototypes, then fitting them into aircraft and debugging the installations, all took too long for the cannon to achieve anything in the Battle of Britain. In the initial Spitfire installation, which did see brief use in the Battle, drum-fed guns were mounted on their side in order to bury as much as possible of the bulky magazine within the wing thickness. The Hispano took a marked dislike to this unfamiliar environment and jammed as often as it fired. Much modification was needed to both the gun and the mountings before acceptable reliability was achieved. Even so, the stoppage rate by 1944 was still three times that of the US .50 Browning.

Work was also needed to the ammunition, as it was found that the fuze of the standard explosive shells was too sensitive, causing them to burst on the aircraft skin rather than within the structure where they would do most damage, and plain steel practice shells often proved more effective. By 1941 both a delayed-action fuze and an explosive with added incendiary filling had been developed, but the practice rounds remained in use alongside the HEIs until they were replaced by a new semi-armour piercing round (SAPI) which was essentially an HE shell filled with an incendiary compound and capped with a hard steel tip instead of a fuze. From 1942 on, the standard Hispano loading became 50% HEI, 50% SAPI.

Types of RAF 20 mm Hispano ammunition, from left: Practice/Ball; HEI; SAPI; AP

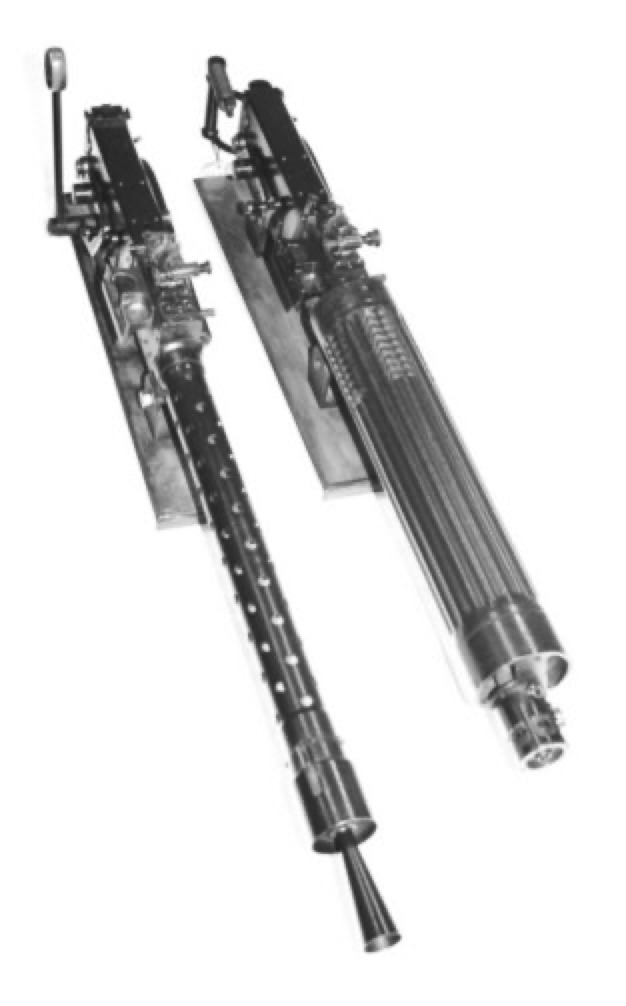

Compared with other Second World War 20 mm aircraft cannon, the Hispano was a powerful and effective gun, but only averagely fast-firing and unusually long and heavy. Its weaknesses were addressed in the late-war Mk V, shortened, lightened and speeded-up from 600 to 750 rpm. The Hispano Mk V could lay claim to being the best aircraft gun of the war, but it mainly saw action in the Hawker Tempest. The RAF armament standard armament of four Hispanos was also probably the best all-round fighter armament of the war, weighing more or less the same as the standard American armament of six .50″ Brownings but being about twice as destructive.

Sadly the same claims could not be made of the RAF’s bomber defensive armament. The RAF had discussed the option of cannon armament when writing the B.12/36 bomber specification, but designed against this in favour of the Browning .303 in power-operated multi-gun turrets. In 1938 it reconsidered this decision, but by then the weight of a turret with 20-mm cannon could no longer be accommodated in existing designs. During the war the .303 gradually lost effectiveness, but various attempts to introduce more powerful guns almost all failed. The long and heavy Hispano did not enter service in turrets until very late. The .50″ Browning was fitted to some turrets by the end of the war.

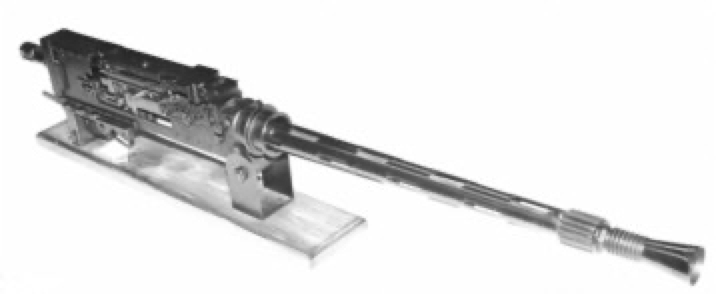

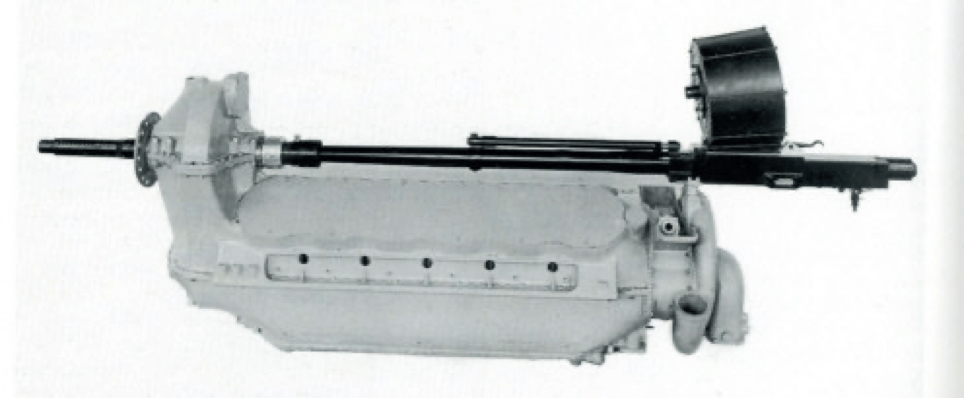

These were not the only guns used by British aircraft during the Second World War. Two others deserve mention; the Vickers 40 mm Class S and the Molins 6 pounder. The Vickers was designed around the same ammunition as the naval 2 pounder pom-pom, but the gun was based on a much-developed 1½ Pdr COW gun. It was originally intended for aerial combat, but this idea was abandoned. When a need arose for a gun capable of penetrating tank armour which could be fitted to ground attack planes, the S gun was dusted off and issued with armour-piercing ammunition.

It saw service in the Hurricane IID (with one slung under each wing) and was an alternate armament for the Hurricane Mk.IV, which otherwise carried rocket projectiles, conversion between the gun and rocket armaments being quite rapid. The S gun performed very well in North Africa, South-East Asia and in 1943/44 over northern France, flying from bases in England. Compared with the rocket projectiles more usually associated with “tank-busting” the S Gun was far more accurate. Unfortunately, it wasn’t powerful enough to penetrate the latest tanks, and the Hurricane Mk.IV was withdrawn from the European theatre only three months before D-day.

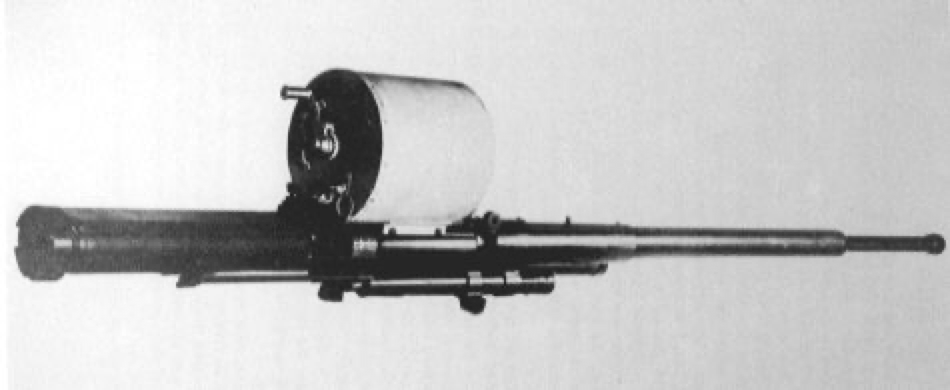

The RAF continued to show interest in airborne anti-tank guns, leading to the development of the DH Mosquito FB XVIII (better known as the Tsetse). This carried an army 6 pounder anti-tank gun fitted with an autoloader developed by the Molins company. This combination worked very well, scoring a 33% hit-rate against tank-sized targets, and the 57 mm ammunition was far more effective than the 40 mm, but the RAF changed its mind and handed the planes over to Coastal Command for anti-U-boat work since it was the only gun which could reliably penetrate a pressure hull. In 1946 a Tempest fitted with a pair of Vickers 47 mm Class P anti-tank guns was tested, but after that official RAF interest in powerful ground-attack guns disappeared for good.

The comparative sizes of RAF 20 mm, 40 mm, 47 mm and 57 mm aircraft cannon ammunition convey some impression of their relative power.

The Modern Era

At the end of the Second World War, there was, as usual, very little money for new armament developments and the Hispano remained in service until the mid-1950s, not just in fighters but also in the Shackleton MR plane.

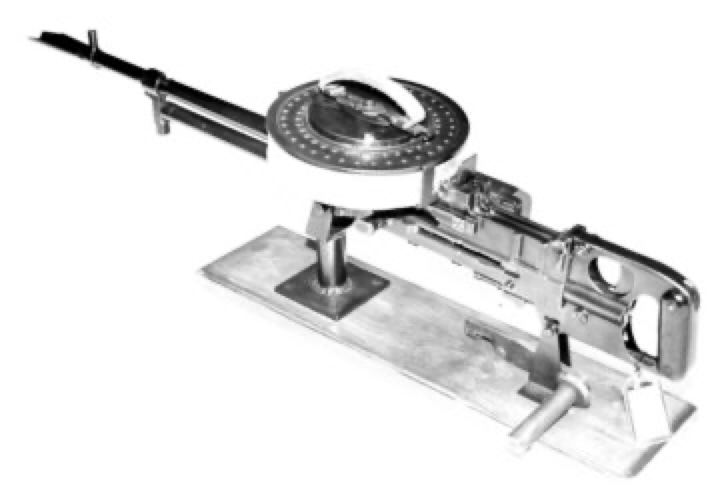

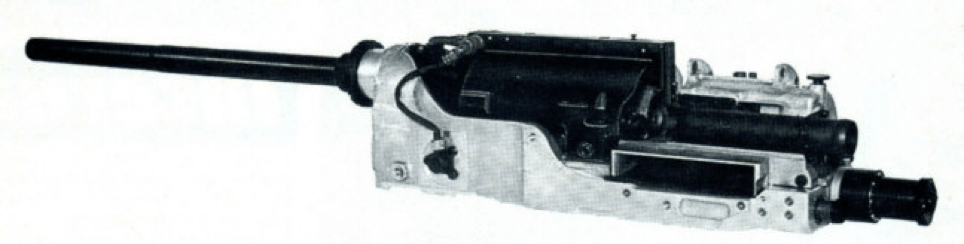

However the Allies did have a new gun to play with, the Mauser MG 213C. The German firm had designed a new type of gun to meet a Luftwaffe requirement for a very fast-firing, high-velocity 20 mm cannon. This addressed the main restriction on rate of fire – ammunition handling – by breaking it down into several stages. Instead of one chamber formed as a part of the rear of the barrel, five chambers were used within a cylinder whose axis of rotation was parallel with the barrel, so that as the cylinder rotated, each chamber was brought into line with the barrel in turn, and its cartridge fired. At the same time, the other chambers were engaged with loading a fresh cartridge or ejecting a spent case. This allowed rates of fire of well over 1,000 rpm to be achieved. As this layout bore some resemblance to the traditional revolver type of handgun, it became known as the revolver cannon. During the development of the MG 213C a low-velocity 30 mm version was also produced, considered more suitable for bomber destruction. This became the focus of interest in both the UK and France, who continued the development of the gun. It took several years before the resulting Aden and DEFA guns were ready for service, but they were eventually introduced using slightly different versions of the 30 mm ammunition.

Further joint development saw the ammunition altered to fire a lighter shell at a higher muzzle velocity, and this became the NATO 30 mm round still used by the Aden Mk 4 and DEFA 550 series guns, and by the M230 Chain Gun used on the Apache AH-64 attack helicopter in British Army service. However, the Aden, DEFA and M230 all use slightly different versions of the ammunition which are not completely interchangeable.

The 30 mm Aden Mk 4 was the standard RAF and FAA gun from the late 1950s until the 1980s, and remains in service with the Hawk trainer (the last combat aircraft to carry it being the Sea Harrier and the Jaguar). It was exceptionally hard-hitting for its day, firing shells weighing twice that of the Hispano’s at an only slightly lower muzzle velocity, but at a much higher rate of about 1,300 rpm. The difference in destructive effect compared with the Hispano was even greater than these figures indicate, because the Allies also benefited from another German development; the Minengeschoss or high-capacity mine shells. When used in the Aden, this resulted in the 30 mm shells having four times the blast effect of the Hispano’s. Aden ammunition also used another German development, tungsten-cored AP projectiles.

The RAF preferred the hard-hitting 30 mm Aden round over the 20 mm weapons favoured on most US combat aircraft. Nevertheless the 20 mm M61 Vulcan rotary gun see British service in the SUU-23/A gunpod which could be carried by the RAF’s Phantom FGR.2 version of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II aircraft.

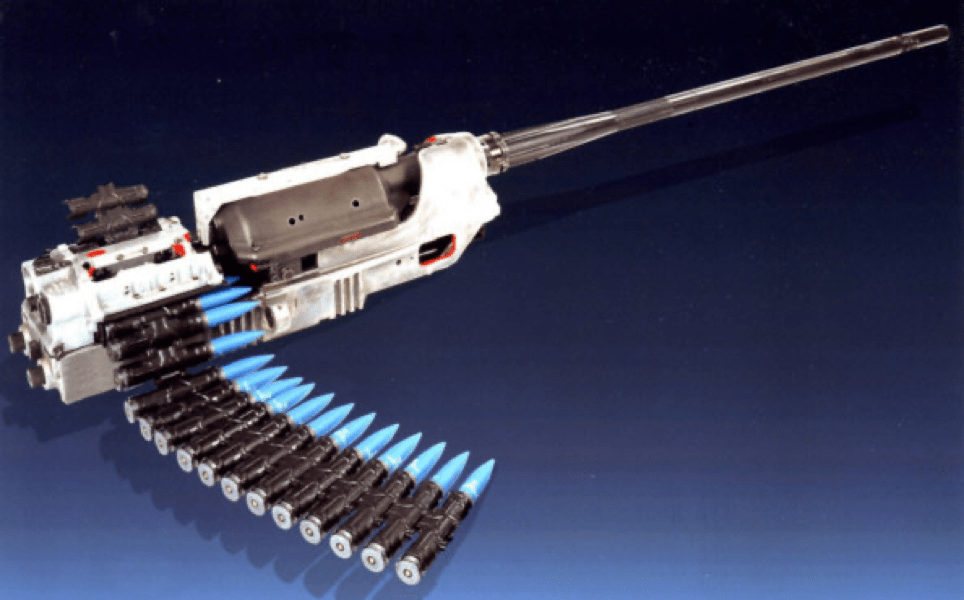

The next gun to enter RAF service was the 27 mm Mauser BK 27 revolver cannon, fitted to the Panavia Tornado aircraft. This is similar to the Aden and weighs very little more, but uses 27 mm ammunition which fires shells of the same weight at a muzzle velocity which is 30% higher and at a rate of fire which is 25% faster, at about 1,750 rpm. The same gun, modified for a linkless feed system, is also fitted to the Eurofighter Typhoon.

In the 1990s there was an abortive attempt to produce a new version of the Aden gun, chambered for the NATO 25 mm cartridge and known unsurprisingly as the Aden 25. It was initially intended to arm the RAF’s Harriers from the GR5 onwards but was defeated by various technical problems, the final and insurmountable one being the sharp curve required of the path of the ammunition belt between the magazine and the gun, which caused unreliable feeding. It was abandoned at the end of the last decade after about 100 guns had been built, and the Harriers have remained gunless ever since, which reportedly proved a disadvantage in Afghanistan.

The picture below shows the ammunition used in RAF guns, plus the 25 mm NATO round which might be introduced into service with the F-35B. Note the two types of Aden ammunition: the early Low Velocity (which was almost identical to the Mauser original) which was soon replaced by the High Velocity, which sacrificed some shell weight to make space for more propellant to raise the muzzle velocity.

From left: .303″; .50″ BMG; 20 mm Hispano; 30 mm Aden Low Velocity; 30 mm Aden High Velocity; 20 mm M61; 27 mm BK 27; 25 mm NATO

Final Observations:

How useful are guns?

In the days before guided missiles, guns were what fighter aircraft were all about: the sole purpose of the aircraft was to get some guns into a position where they could harm the enemy. The introduction of guided air-to-air missiles led to the introduction of missile-only interceptors in the 1960s, which was promptly regretted when experience in Vietnam revealed that the impressive missile hit rates achieved in trials were not replicated in combat, and guns could still be useful. Since then, missile performance, in both the air-to-air and air-to-ground roles, has greatly improved.

Even so, new fighter designs still come with guns – or at least, a gun. This despite the problems which their vibration and noxious gas emissions cause to the aircraft, as well as the cost in purchasing, feeding and maintaining the guns plus training those who use and care for them. Indeed, the Ministry of Defence did its best to cancel the acquisition of the guns for the RAF’s Typhoon, but these were eventually fitted and cleared for use, at least in the ground attack role. For the F-35B Lightning II a gun pod with the GAU-22/A 25-mm rotary cannon is available, but the UK has not yet purchased this and has expressed no interest in doing so.

Is there still a role for guns on combat aircraft? I think there is, for several reasons. They enable aircraft acting in close support of troops to deliver very precise fire which is limited in effect, so that enemy forces very close to our troops can be engaged. Guided bombs and missiles, while precise, have a considerably greater radius of destruction. A gun also has the ability to fire warning shots or inflict limited damage – to a ship, for instance – in a display of determination. In the air-to-air role, a gun may also fire warning shots (when using tracer ammunition), may be used to destroy low-value targets such as drones, and provides a last-ditch backup should the missiles run out.