The Eye of History

The history of a war is mostly written after its end. That historical context necessarily affects any conclusions that one may draw from it. In the case of WWII, the conflict lasted about six years (it could be years longer or shorter, depending on where you lived) and the strategic bomber offensive was impactful mostly in its last year, from mid-1944 onwards. By then the commanders in Europe had finally settled on the most crucial targets (fuel and transportation), air superiority had been won, radar navigation aids introduced, and a huge force built up. For example, from mid-1944 onwards RAF Bomber Command dropped about 50,000 ton of bombs per month; in 1943 its average was about 13,000 tons and in 1942 it had been less than 4000. Roughly in the same time frame in the Pacific, the USA finally established logistically viable island bases for its new B-29 force, which would devastate Japanese cities. The future perceptive on the bomber offensives of WWII would be coloured by that last year of war.

They were also coloured by the nuclear bomb. Conventional bombing during WWII certainly demonstrated its potential to cause unprecedented destruction to cities and infrastructure, but its was an enormously expensive weapon, requiring repeated and sustained attacks by large numbers of aircraft, manned and serviced by a large force of men, operating from numerous airfields. For all the cost of developing fission and later fusion bombs, they made mass destruction economically viable, if not exactly cheap. It is hard to imagine that the post-war air forces would have retained the huge fleets of strategic bombers that were necessary to inflict this level of damage by conventional means.

The perspective of 1943 would have been a different one. Four years into the war, the strategic bombing offensive was still a gamble, trading often unsustainable losses for dubious benefits. At no point did the Allies seriously consider abandoning the strategic offensive of the heavy bombers, as this would have been unacceptable in both domestic and foreign politics. But the claims of its advocates that it would be war-winning strategy looked unreliable at best. Neither industrial targets such as the German ball-bearing industry nor city targets such as Berlin did deliver on their promise. At most, attacks on enemy industrial targets seemed to slow down the growth of their industrial capacity.

And regardless of their merits, for many air forces heavy bombers were a luxury that they could not afford. In contrast, medium bombers were essential weapons to support ground and naval offensives. They could be built and deployed with much greater ease, were suitable and effective against tactical and operational targets, and could be repurposed to support naval operations. Their greater ability to be based near the front and moved from one base to another as forces advanced (or retreated) ensured a much shorter reaction time. Range appeared to be their major limitation, with a few exceptions such as the G4M. But until good long-range escort fighters were available, the effective reach of an air force was limited more by its fighters than by its bombers.

The End

The medium bomber, as a class, would gradually disappear after the end of WWII. During this conflict, fighters had become substantially larger and more powerful, with a growing ability to carry significant bomb loads to tactical targets. Early jet engines would temporarily brake that trend, because although they allowed much higher speeds to be achieved at high altitude, they did not deliver much trust at low speed. But within a decade, jet engines produced enough trust to power big high-performance fighters, which were also so costly that any air force had to think hard about the number of types in its inventory.

There was a brief period of grace in which a medium-sized jet bomber still had its place. As long as fighter aircraft were subsonic and primarily armed with guns or unguided rockets, a well-designed jet bomber might well be able to evade interception. Cruising at high altitude and high subsonic speed, it was a difficult target for fighters that had very little speed margin over it and often could not climb to the same altitude. A concept which was validated during the cold war by the use of medium-sized US jet bombers for illicit and highly dangerous reconnaissance missions over Soviet territory.

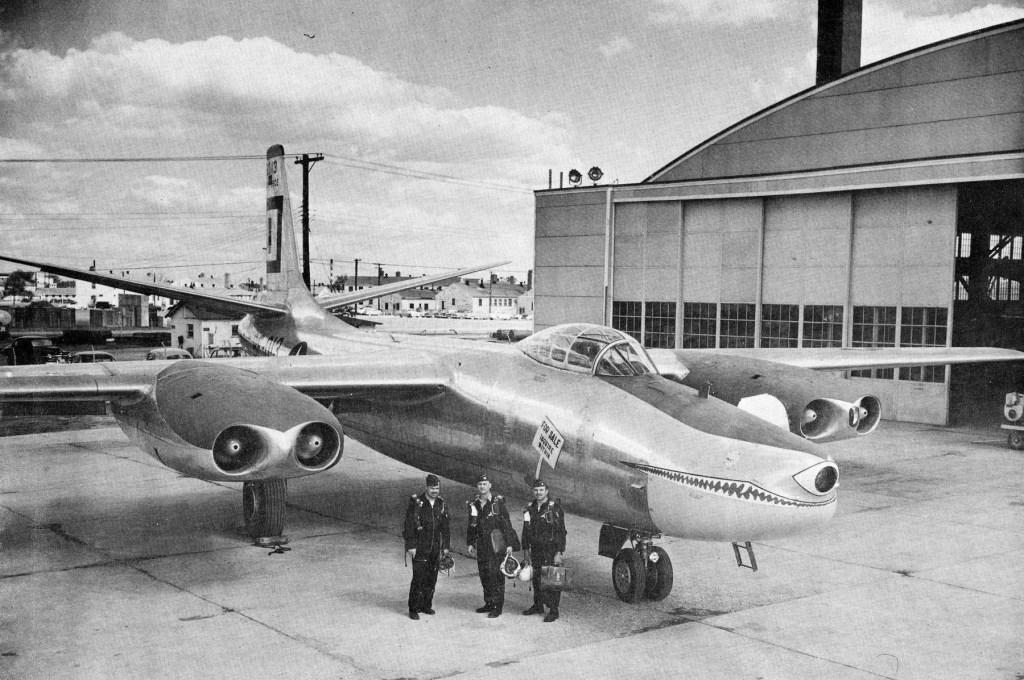

That included the North American B-45, designed as a jet bomber with a minimal development risk and fast entry to service, with a straight laminar-flow wing and four engines in paired wing nacelles: At first J-35s, quickly enough replaced by J-47s. Regarded as an interim type until the far more advanced Boeing B-47 entered service, the B-45 was delivered in 1948 and remained in service until the late 1950s, acquiring notoriety primarily in the RB-45C reconnaissance version.

The B-45’s replacement was the Martin B-57, an Americanised version of the British English Electric Canberra, which the USAF had preferred over Martin’s own B-51 design. The British Canberra had first flown in 1949, and entered service in 1951. In its country of origin, the Canberra replaced the older piston-engined bombers and proved largely immune to interception until swept-wing jet fighters were introduced. The American version entered service in 1954, due to the need to make numerous modifications for an envisaged tactical role. The B-57 would participate in the Vietnam war, and soldier on in highly specialised roles until 1982. Again reconnaissance models (the RB-57D, RB-57E and the radically modified RB-57F) would make a significant contribution to aerial espionage. The same happened in the UK, where heavily upgraded reconnaissance versions of the Canberra were only retired in 2006!

Meanwhile, the US Navy had sought to defend its relevance in the nuclear age by adopting a carrier-borne, long-range, nuclear strike aircraft. The first attempt was the North American AJ Savage, powered by two R-2800-44W piston engines and a J-33-A-19 piston engine in the tail. It entered service in 1949 but was never a major type, as only 55 were completed, and many were later converted to reconnaissance aircraft or flying tankers. The AJ was an interim aircraft as Douglas was already working on a vastly more advanced, swept-wing, twin-jet carrier bomber: The Douglas A3D Skywarrior. Delivery of the A3D-1 began in 1956 with the A3D-2 following in the next year. The USAAF warmed to the type as a potential alternative to the B-57 and ordered its own version of it as the B-66; deliveries began in 1956. In what is developing to be something of a theme here, the B-66 was primarily used as RB-66 reconnaissance aircraft, EB-66 electronic warfare platform, or WB-66 weather reconnaissance aircraft. Only a small number of the B-66s were built to be used as bombers. The Navy too, quickly discovered the value of the A3D in these specialised roles, as well as using the “whale” as aerial tanker.

Meanwhile, although a small number of Tupolev Tu-14 twin-jet bombers were built as torpedo-bombers, the most numerous Soviet contribution to the class was the Ilyushin Il-28 “Beagle”, with a straight wing and two VK-1 engines, derivatives of the Rolls-Royce Nene. First flown in 1948, the Il-28 was built in large numbers compared to other early jet bombers, widely exported to the USSR’s allies, and built in China as the Harbin H-5. It remained in service in the 1990s. (And probably even today in North Korea.) Its fundamentally outdated design appeared to be no barrier to its continued usefulness. Unsurprisingly, there were reconnaissance and electronic warfare models, and the type seems to have been much used as testbed.

Much less numerous were the bomber versions of the Yakovlev Yak-28 family. The lineage of this aircraft started with the Yak-25 heavy fighter of 1952, which was subsonic; the Yak-28 bomber model was derived from the supersonic Yak-26 prototype of 1955. The Yak-28 “Brewer” entered service in 1960 and its performance was good enough that interceptor versions of the basic airframe would also enter service, being dubbed “Firebar” by NATO. Although a remarkably cool-looking family of aircraft, they have a fundamentally outdated layout, which reportedly caused numerous aerodynamic issues, and they were only produced in modest numbers.

A similar fate befell the Sud-Ouest SO.4050 Vautour, a twin-engined, swept-wing multi-role aircraft which served briefly with the French air force. On paper, the Vautour would be as versatile as the Mosquito, and serve as bomber, nightfighter, attack aircraft, and reconnaissance aircraft. Underpowered and with a relative primitive standard of equipment, the type never matched these high hopes. Only 149 were built. Of these 31 were sold to Israel, which briefly used them in combat, with good results.

The medium bomber class as a whole was displaced by fighter-bombers and attack aircraft both in its old reason of existence, tactical bombing and interdiction, and its possible new reason of existence, nuclear bombing. The fundamental reason was that in the 1950s, there was a major jump in the size and complexity of fighters and attack aircraft. The supersonic F-100 had nearly twice the empty weight of the subsonic F-86. Such airframes had the capability of taking over what had once been bomber tasks, and because of their exponentially rising cost, engineers and officers had a strong incentive to embrace this potential.

But besides that, the changing air combat environment meant that the mission profiles once flown by medium bombers were becoming too dangerous. The appearance of guided missiles, even if their actual performance initially fell far short of that advertised, changed tactical thinking. If anyone designed an specialised airframe for medium-range bomb delivery, it would no longer look like a traditional bomber, simply because that layout was no longer a good match for requirements. Designs such as the LTV A-7 Corsair II or Grumman A-6 Intruder were much more survivable in the new environment.

Several of the jet bombers lasted for a while because roomy fuselages and good high-altitude performance made them excellent platforms for a variety of special roles. Four extra crew members could be accommodated in an EB-66, bringing the total to seven: You could not do that with a fighter-bomber. This, however, also changed as electronics became more compact and computers more capable. Besides, for these non-combat roles small airliners and transport aircraft proved to be good alternatives.

As the medium bomber faded away, its history faded away with it.