Italian Impasse

In late September 1940, aircraft of the Corpo Aero Italiano arrived on bases in Belgium to participate in the Battle of Britain. The core of this corps consisted of two Stormi of 43 Fiat BR.20M twin-engined bombers each, a Gruppo of 50 Fiat CR.42 biplane fighters, and a Gruppo of 45 Fiat G.50 monoplane fighters. There were also five CANT Z.1007bis three-engined reconnaissance aircraft, which would be used as bombers. This small force would not achieve anything commensurate to its losses. A first night bombing mission by 17 Fiat BR.20M bombers resulted in the loss of three aircraft, of which one crashed after take-off and two were abandoned on return because their crews failed to find an airfield to land on: Their aircraft lacked modern radios and navigation equipment. Consequently, the CAI decided to bomb in daylight, using small formations with a strong fighter escort. After a few missions that were fortunate enough to encounter little opposition, a raid on Harwich on 11 November resulted in the loss of 3 out of 10 bombers. RAF pilots observed that the defensive armament of the BR.20M was ineffective (the Italians reported that their guns were frozen in the intense cold) and it lacked armour protection. The escort of 40 CR.42 fighters was no match for the attacking Hurricanes. The CAI returned to sporadic night bombing missions, until they were called back in early 1941. Lack of experience and of suitable equipment to operate in a cold climate and at night had been serious handicaps, and the BR.20M proved an obsolescent bomber.

The Italians had three primary bomber types in production at the time: The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79, the Fiat BR.20M, and the CANT Z.1007bis. The older SM.81 was still in service, and the SM.84 was in development. What was unusual, at the time, was that the Savoia-Marchetti and CANT bombers were tri-motors. The three-engined configuration had been popular before 1930, but had fallen out of favour by the outbreak of WWII, as more powerful and more reliable engines appeared, and a higher value was assigned to clean aerodynamics.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, Italy fell behind in the development of aircraft engines. A look at the 1938 edition of Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft suggests no immediate reason for alarm. For example, Fiat was offering the 1000 hp 18-cylinder A.80 RC41, and Piaggio the 14-cylinder 1000 hp P.XI RC40 radial. At the time these were, on paper, reasonably competitive with the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 and Wright R-1820. However, the A.80 was only available with a single-speed single-stage supercharger, which meant that its best performance was available at an altitude of 3000 to 4000 m. The P.XI was a licensed version of the French Gnome-Rhone 14K, and while versions of it would be developed with improved supercharging to obtain better altitude ratings, these don’t appear to have seen service. The situation was even bleaker for in-line liquid-cooled engines, because a preference for air-cooled radials had been expressed in 1933. While the advanced Fiat A.38 remained in development, Italy would finally opt for license-producing German engines. The country had talented engineers and some excellent R&D facilities, but did not succeed in bringing more powerful engines to production. One result was that the Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 bomber was built with three radial engines of about 750 hp each for Italy, but offered as a twin-engined bomber for export, with the S.79JR for Romania having two 1220 hp Jumo 211Da engines: More power for less weight.

Another handicap for the Regia Aeronautica was that Italian strategy was all over the place. The Duce’s approach to war appeared to take the sporting view that participating was more important than winning. Italian forces were scattered all around the compass, with environmental and operational requirements that widely diverged between far-flung locations such as the horn of Africa and the Caucasus. Giving their limited industrial means, a far more logical strategy for the Italians would have been to focus on dominating the Mediterranean Sea, for which purpose their country enjoyed an excellent strategic position. Indeed Mussolini did want to revive the proud Roman name Mare Nostrum, our sea, for the Mediterranean. But embarrassingly enough Axis operations in it came to depend heavily on a German unit, X. Fliegerkorps, based in Sicily. It is not that the Italian air force did not contribute, and in particular it developed torpedo bombing to a high level. But it was never strong enough, and its Achilles’ heel was poor coordination between the air force and the navy.

The SM.79 (or S.79) Sparviero was the most famous of the Italian bombers. It had been sketched in 1933 as a fast eight-seat transport of mixed construction, with a wooden wing and a steel tube fuselage structure. The prototype flew with three Piaggio P.IX RC40 and later with Alfa Romeo 125 RC38 radials, and in 1935 set world speed records for 1000 and 2000 km closed circuits. At the time the air force was seeking a modern twin-engined bomber, which would result in the selection of the Fiat BR.20, but general Valle, as chief of staff, pushed through an order for a small number of S.79 bombers. A prototype bomber, with Alfa Romeo 125 engines, was ready in 1936. This was noteworthy for the addition of a dorsal “hump” which contained both a dorsal gunnery position and a fixed forward-firing gun. For the bombardier, a ventral fairing aft of the wing was added, with a flat aiming window in front. When the bombardier occupied this position, separate fairings to accommodate his legs and knees would extend. Because of its civilian origins, the S.79 was compromised bomber, and criticised for its overall configuration, small bomb bay, inadequate defensive armament, and lack of means for the crew to communicate effectively with each other. But it was fast, and it was available and reliable, while the preferred Fiat BR.20 was delayed and would need lengthy troubleshooting before it became effective. Besides, the SM.79’s mixed construction was something Italian industry was familiar with.

A total of 99 SM.79s were sent to fight in the Spanish civil war. There it made a good impression, because its speed was often sufficient protection. When Italy entered the Second World War on 10 June 1940, the air force had 612 of these aircraft on strength, which made up 14 of the existing 23 bomber Stormi. The first production series had 750 hp Alfa Romeo 126 RC34 engines and a defensive armament consisting of three 12.7 mm Breda-SAFAT guns: A dorsal gun in the hump behind the cockpit, a ventral gun at the back of the ventral gondola, and a fixed forward-firing gun in the front of the hump. Initially, a single .303 Lewis gun was added to fire from the beam windows left or right, but later a 7.7 mm Breda-SAFAT was installed in each window. During WWII this proved insufficient to defend the S.79 against attack by modern fighters, and initial combat experience with the aircraft was unfavourable. The career of the S.79 was largely saved by its good performance as a torpedo bomber. A first experimental unit entered combat in August 1940, and the conversion proved a success. A single 800 kg torpedo was carried under the fuselage offset to the left. Good low level performance was further boosted in the spring of 1943 by installing Alfa Romeo 128 RC18 engines rated to give their best performance at 1800m, and the elimination of the now superfluous ventral gondola. These changes, and an increase in fuel capacity, created the SM.79bis. Commonly, 12.7 mm guns were installed in the beam windows of later aircraft.

Savoia-Marchetti did try to improve on the SM.79, and failed. In 1938 the Regia Aeronautica had requested a better bomber, aiming for a range of 2600 km, a bomb load of 1000 kg, and a speed of 530 km/h. Savoia-Marchetti’s initial response was to take a SM.79 off the production line and fit it with 1000 hp Piaggo P.XI RC40 engines and twin tail fins. Further refinement resulted in many changes, most obviously the replacement of the dorsal ‘hump’ by a simple gun turret, while internally room was made for a substantial bomb bay. Superficially, such changes addressed the major known weaknesses of the SM.79, but the SM.84 was also a substantially heavier aircraft. The SM.84 may have been a better bomber on paper, but the SM.79 was a better torpedo bomber thanks to its greater agility and more reliable engines. It outlived its planned successor. Only 309 SM.84s were completed, against 1217 SM.79s.

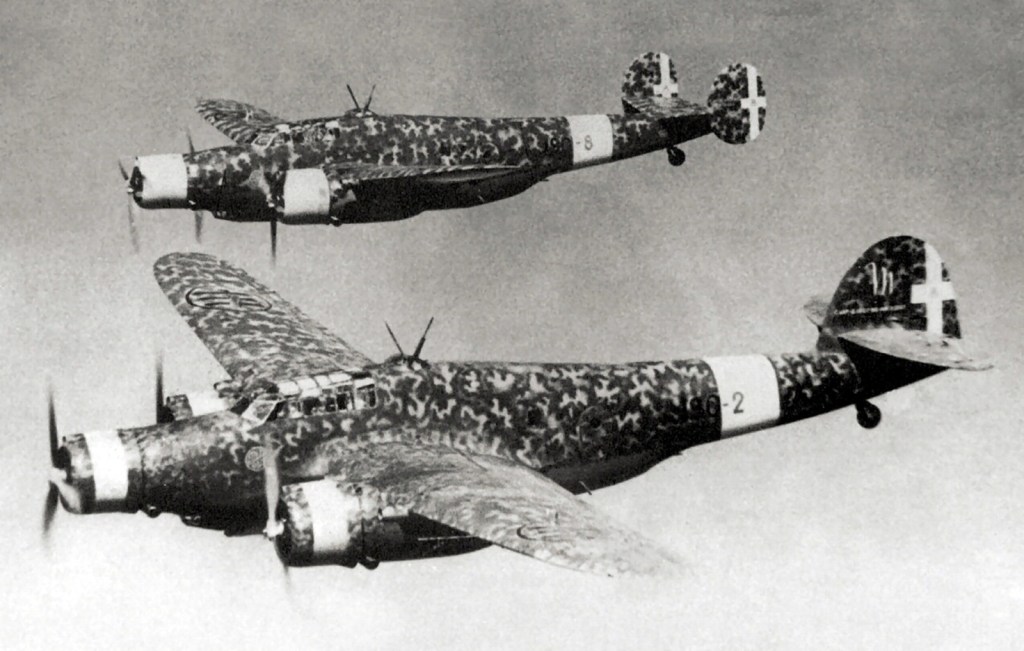

On paper, probably the best Italian bomber was the CANT Z.1007bis. In the 1930s, CANT had built prototypes both of a twin-engined bomber, the Z.1011, and of the three-engined Z.1007. The latter owed much to the highly successful Z.506 seaplane and was the type preferred by the air force. This original CANT Z.1007 was a sleek three-engined aircraft powered by Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI RC15 engines. But this liquid-cooled V-12 failed to deliver the promised power. When a small series of Z.1007 bombers was built with Asso XI RC40 engines, the air force calculated that they delivered 836 hp instead of the nominal 1000 hp.

This prompted a redesign of the aircraft around the new 1000 hp Piaggio P.XI radial. This evolved into much more than an engine change and the Z.1007bis became a substantially larger aircraft, although the wing span remained 24.80 m. With an empty weight of 9,396 kg and a loaded weight of 13,621 kg the Z.1007bis was in the weight class of the Ju 88A, but its bomb load was 900 kg. This was an improvement over the 500 kg of the original Z.1007, but still modest, although it could carry that load over 2000 km. Defensive armament was fairly modest too, with a ventral Scotti 12.7 mm gun, two Breda-SAFAT 7.7 mm guns firing from lateral windows, and a basic Lanciani Delta 1 dorsal turret with another 12.7 mm Scotti. Most WWII aircraft turrets relied on power drives to overcome the air drag acting on the gun barrels, but the Lanciani Delta 1 instead had a rod sticking out from the back of the turret to balance the drag force acting on the gun barrel! Some later aircraft had the more advanced Breda V turret instead. Also during the production run, twin tail fins were introduced instead of the original single fin, but this did not prompt a designation change. The Z.1007ter had more powerful Piaggio P.XIX RC45 engines and other updates.

The Z.1007bis was popular with its crews, because it had better performance than the SM.79 and excellent handling characteristics. It was of wooden construction throughout, which appears to have caused durability issues, as the airframes deteriorated in the warm and humid Mediterranean climate. The biggest problem was the painfully slow delivery of a total of 581 aircraft divided over 34 Z.1007, 502 Z.1007bis, and 89 Z.1007ter. Even so, shortages of essential equipment such as instruments, oxygen breathers and bomb sights plagued the units. The combination of slow production and fairly high loss rate meant that the Z.1007 was never available in substantial numbers.

Chief designer Emilio Zappata had redesigned the Z.1007 to have metal construction in the form of the Z.1015, but this aircraft was in turn superseded by the twin-engined Z.1018, a more modern and elegantly streamlined design. It needed more powerful engines, but the 1350 hp Piaggio P.XII RC35 selected for production aircraft proved troublesome. Long development and slow production curtailed the production to 8 aircraft. Somewhat bizarrely, CANT was asked to produce a wooden version in parallel, the Z.1018A, perhaps because the company was more familiar with wooden construction. It managed to complete 10 of those. That CANT designed and built six substantially different bomber airframes, and delivered some 600 production aircraft for all this effort, illustrates the inefficiency of the Italian war effort.

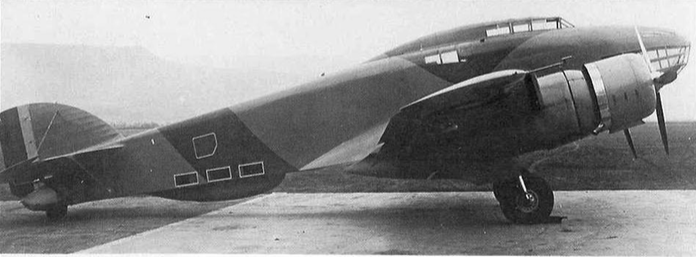

The bomber the Regia Aeronautica had originally wanted was the Fiat BR.20. It had written a requirement for a fast, modern twin-engined bomber that would be competitive with the best foreign designs. And when the BR.20 entered service in 1936, after a fairly quick and painless development, it was a modern design. Of all-metal construction and powered by two 1000 hp Fiat A.80 RC41 radial engines, the BR.20 featured rifle-calibre Breda-SAFAT guns in a nose turret, a ventral, and a dorsal gunnery position. Its defensive armament would be repeatedly upgraded during its service life. It had a range of 2000 km and a maximum speed of 425 km/h, which was good for the mid-1930s. A bomb load of 1600 kg made it, by Italian standards, a heavy bomber. Like other Italian aircraft, it performed well in Spain. In 1938 the Japanese purchased about 80 to fill a gap in their own bomber production plans, but retired them quickly.

The problem was that the design aged rapidly and wasn’t modernized to a degree that could have kept it competitive. There was a modest upgrade in the form of the BR.20M with improvements in armament and aerodynamics. A more thoroughly improved BR.20bis was only built in very small numbers. When Italy declared war some 250 of these Fiat bombers were available, and total production would run to only 606. They proved vulnerable in every theatre of operations they were sent to, which included the brief participation in the Battle of Britain described above, and a campaign in Russia. Perhaps that the biggest problem of the BR.20 was that its performance naturally assigned it to level bombing missions, for which the Italians could spare only a weak force and had no effective escort fighters.

Yet another type built in Italy was the Ca.135, built by Caproni-Bergamasca, a subsidiary of the Caproni firm. The original Ca.135 of 1936 was powered by Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI in-line engines, which were as disappointing in the Ca.135 as they were in the Z.1007. The same change to a Piaggio P.XI radials imposed itself. The Regia Aeronautica still judged the type to be inferior to the SIAI-Marchetti and CANT competitors, and deemed it unfit for operational service even its improved Ca.135bis version. But the Ca.135 did see combat during WWII, as Hungary acquired most of the aircraft built, reportedly a total of 67. Six more were exported to Peru. Caproni would have much more success with a family of light bombers and multi-role aircraft, that ran from the Ca.309 colonial bomber-transport to the Ca.314 light bomber and Ca.316 floatplane.

Low production numbers are the common theme in the story of Italian bombers. The country did also build a four-engined heavy bomber, the Piaggio P.108B, but so few of these were available that its operational missions all were flown by four aircraft or less. Hardly a decisive force, and clear evidence that the heavy bomber was a mismatch for Italian industrial capacity! What the Regia Aeronautica needed most was an affordable and versatile medium bomber suitable for naval missions, and it appears that, despite its age, the robust SM.79 met that need best.

The Commando Supremo site is an excellent resource if you wish to read more detail on the Italian aircraft of WW2.

Next: Japanese Competitors