Soviet Hesitations

When Germany attacked the USSR in June 1941, the Soviet military was deeply committed to a process of expanding and absorbing new equipment. As in the case of France in 1940, this made it vulnerable. Much of the new equipment available could not be effectively used because of a lack of training, supplies, and appropriate tactics. Thus the bomber force still depended heavily on the old twin-engined SB, which by 1941 was vulnerable to modern fighters, and the even older TB-3 heavy bomber. The production of newer types would be disrupted by the German invasion and the need to relocate much of the industry to the east, beyond the reach of the enemy. The advance of German forces deep into Soviet territory created a strong demand for tactical aircraft to help stabilise the frontline and push back the enemy.

One of the consequences was that the production and use of heavy bombers was severely restricted. A modern four-engined high-altitude bomber for strategic applications had been designed in the mid-1930s, based on the unusual idea of using a fifth engine buried in the fuselage to drive a supercharger that would supply air for the four engines on the wings. The Tupolev ANT-42 flew in late 1936, with four Mikulin M-34FRNB engines and a single Klimov M-100 driving the ATsN supercharging system. The ANT-42 looked very promising when it finally entered production in 1939 as the TB-7, but it quickly ran into problems. Only a few were completed with the ATsN unit and M-34 engines, which proved troublesome. A search for alternative engines began that would eventually result in aircraft being built with Charomsky M-30, M-40 or ACh-30B diesel engines, Mikulin AM-35 in-line engines, and Shvetsov M-82 radials! Frequent design changes, technical problems, and a low priority constrained the production to only 93 aircraft in total. The heavy bomber, later renamed Petlyakov Pe-8 in honour of its chief designer, had an evident propaganda value. It made a name for itself by attacks on Berlin in August 1941, and its later use to fly dignitaries to the UK and USA. Production and operational use continued into 1944, but the production rate was too low to build up a strategically significant force, or indeed to compensate for increasing attrition.

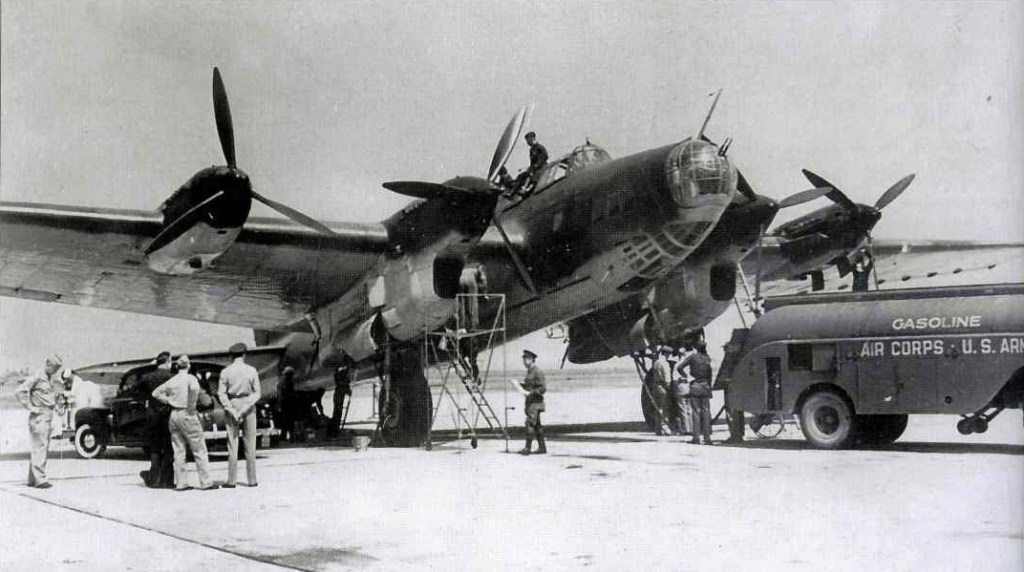

Nor did the USSR acquire heavy bombers through lend-lease to compensate for the gap in its own arsenal. (The shortage of Pe-8s was compensated for in part by acquiring B-25s.) The potential of using bases in the USSR for attacks on German industry in the East was significant, and in 1944 this was exploited by Operation Frantic, which provided bases in the USSR near Poltava for American heavy bombers on “shuttle” missions. But this too remained a limited effort, marred by mutual suspicions between the allies and a successful German attack on the bomber bases.

That said, that the USSR did not have a substantial heavy bomber forces did not imply that it had no interest in long-range bombardment missions. But it tried to meet the need by using smaller twin-engined types. Chief among them was an aircraft designed by Sergei Ilyushin. The starting point was the TsKB-26 of 1935, of mixed construction and more a technology demonstrator than a prototype. This was followed by the all-metal TsKB-30 in the next year. Ilyushin’s design set new standards for performance, thanks to careful streamlining, a high-aspect ratio wing with a relatively high wing loading, and new M-85 radial engines. (The M-85 was a licensed version of the French Gnome-Rhône 14K Mistral Major). The TsKB-26 set several world records, and the TsKB-30 was quickly accepted for production, which began in 1937 with the designation DB-3. At the time the DB-3 was one of the best bombers of the world, with good handling and excellent performance. It had a range of 3100 km with a 1000 kg bomb load, and 4000 km with 500 kg. In the next years, the M-85 engines were replaced first by the M-86 with an improved supercharger drive, and then the M-87 with a two-speed supercharger.

In 1939 the first flight was made of a new version that was initially known as the DB-3F and later as the Ilyushin Il-4. Visually this was easily distinguished by its longer and more streamlined nose, which improved the ergonomics of the navigator’s position. Less noticeable were a new wing with a larger area and thinner profile, a new fuel system, an improved undercarriage, improved installations of the defensive armament, new engines, and detailed design changes to support mass production. The DB-3F was a bit faster (445 km/h at 5400 m vs 428-436 km/h at 4960 m), had a slightly longer range (3500 km vs 3100 km with a 1000 kg bomb load), and was overall a better aircraft to fly and operate. On the other hand the engine was the M-88, of which production was disappointingly slow, while too many of those that were built failed acceptance testing. For a while in 1940 the air force even stopped accepting M-88 engines entirely. The later M-88B version was more reliable, but still had a service life of only 150 hours.

Nevertheless the USSR had 310 DB-3 and DB-3F bombers in service at the outbreak of war, the bulk of the modern bombers of the long-range bomber force. The evacuation of plants to the east disrupted production in the second half of 1941, but later sufficiently high priority was given the type to complete 1,528 DB-3s and 5,256 DB-3Fs or Il-4s, making the type the backbone of the long-range force for the duration of the war. Wartime changes included the introduction of a taller dorsal turret with a heavy machine gun, addition of a fourth crew member to man a ventral gun position, increased use of wooden parts because of aluminium shortages, and changes in the wing structure to cope with a shift in c.g. and increase fuel capacity.

While the Il-4 was the most numerous long-range bomber type for the duration of the war, there were other attempts to develop long-range twin-engined bombers. Several of these involved the use of diesel engines. Diesel engines were not generally favoured for aviation applications because they needed to be strongly built and were heavy, but they are relatively fuel efficient, making them attractive for long-range aircraft. In the 1930s two large diesel engines entered production, the M-30 and M-40. These were similar in many respects as both were derived from the earlier AN-1RTK, but the M-30 was developed by a team of imprisoned engineers under supervision of the NKVD, while the M-40 was developed at TsIAM, the Central Institute of Aviation Motor Construction. Neither was very successful, with one serious problem being that they were difficult to restart at altitude. In June 1942 A.D. Charomskiy, one of the engineers who worked on the M-30, was released from prison and made head of his own design bureau, which developed the improved ACh-30B.

The ACh-30B powered the two prototypes of the Il-6, which inherited the general layout of the Il-4 but as a larger aircraft. The Il-6 was not further developed. The diesel did, however, have modest application in the Yermolayev Yer-2. The complicated history of this aircraft began with the Stal-7, a small all-metal airliner designed by Roberto Bartini, an Italian communist engineer who migrated to the USSR after Mussolini established a fascist dictatorship in Italy. This created interest in a bomber version, but Bartini would not be involved in its design because in January 1938 he too was arrested and imprisoned. Design leadership was taken over by Vladimir Yermolayev. (Different transliterations of his name abound, as the correct transliteration of the letter E of the Cyrillic alphabet is a surprisingly complex problem.) Reportedly, Yermolayev earned Stalin’s trust by taking his slide rule out of his pocket when then the dictator asked him about the performance of the new bomber, and calculating the answer on the spot.

The DB-240 retained only the overall configuration of the Stal-7. It was a quite distinct shape in the skies, with an inverted gull wing (which helped to keep the landing gear short), a fuselage of rounded triangular cross-section, an extensively glazed nose, a pilot’s cockpit offset to the left, and twin tail fins. On paper, the design offered good performance and a longer range than the DB-3F, with the significant advantage over its competitor that it could carry four bombs of 250 or 500 kg in its internal bomb-bay. Unfortunately, the intended engine was the Klimov M-106. This engine never matured and the prototypes flew with the less powerful M-105. With these the DB-240s was underpowered, and in November 1940 an air force technical committee bluntly stated that this version was only acceptable as a transitional type, while chiding the design bureau for submitting overly optimistic performance estimates and misleading test results. A small series of 70 aircraft was nevertheless ordered while the OKB was instructed to study more powerful engines, such as the Mikulin AM-37, the AM-35A, or the M-40 Diesel engine. In December 1940 the type was renamed Yer-2 but production encountered delays, and only 13 had been received in May 1941. At the time of the German attack, it equipped two long-range bomber regiments with a total of 60 aircraft, but the Yer-2 was far from combat-ready and attrition due to technical problems was high. Replacements were not available as in August 1941 the production was halted in favour of the Il-2.

Meanwhile, efforts to find more powerful engines resulted in the evaluation of four aircraft with the Mikulin AM-37, but although this version was fast, it had too many technical issues, and this engine also failed to enter production. Fortunately, the Yer-2 proved adaptable to Diesel engines. Initially the complex and not very successful M-40F was considered but in September 1942 an aircraft flew with two M-30B engines. An evaluation was favourable, because thanks to the good specific fuel consumption of the Diesel engines, the operational range was extended to 5000 km. Hence in late 1943, when the war situation had changed to be much more favourable for the USSR, the aircraft was put back in production with the ACh-30B. The new model was heavier, with a new and larger wing, stronger undercarriage, and improved defensive armament. Some were modified to add a co-pilot to the crew, reportedly because this feature was appreciated on the B-25. In early 1944 the Yer-2 entered operational service again and proved moderately successful, but because production rates were low and technical problems remained unsolved, it never was a major type. It wasn’t particularly well-armed, sticking to the pre-war pattern of a gun in nose, dorsal and ventral positions, although the dorsal gun was now a 20-mm ShVAK cannon in a TUM-5 powered turret, and the nose and ventral guns were 12.7-mm Berezin UB guns. Compared to the Il-4, the Yer-2 was slower and had a lower operational ceiling, but its operational range was better: 5500 km against 3500 km, no doubt in large part because of the lower specific fuel consumption of the Diesels. Production rates were briefly increased after the end of the war in Europe, presumably because the Yer-2 was deemed suitable for the expected offensive against Japan, but in August 1945 it was finally cancelled.

The Soviet long-range bomber force, known as the ADD, never rose to the same scale of ambition as the British and American strategic forces. The reality of a bitter land war fought over the large expanse of European Russia and Eastern Europe created an imperative demand for tactical aircraft, which resulted in the mass production of dedicated ground-attack aircraft such as the Il-2. Entirely in line with this, the most produced twin-engined bomber was the Petlyakov Pe-2, which had started out as a dive bomber development of an experimental high-altitude fighter. This evidently was a drastic change of requirements that required major redesign, but in the summer of 1940 the reports of German successes in France and the study of the Ju 88 (of which the USSR had obtained an example) created a sense of urgency, and Samolyet 100 had the merit that it had already flown and demonstrated good performance. The decision forced the imprisoned engineers of the NKVD-controlled “special design bureau” to work night shifts to complete new drawings in the required 45 days. This rushed program predictably caused numerous teething troubles, so that only a small number of Pe-2s were operational at the time of the German attack in June 1941. The type largely failed as a dive bomber but quickly proved its value as a light bomber, with a speed at low altitude that made it hard to intercept, and a bomb load of 600 kg (maximum 1000 kg). The VVS would receive 10,574 Pe-2s during the war. The “Peshka” was a versatile tactical aircraft, but its fighter origins made it too small to fill a medium bomber role. The gap in the Soviet arsenal was filled in large part by Lend-Lease supplies of the American A-20 and B-25 bombers.

A better medium bomber was under development, by another imprisoned design bureau, this one headed by A. N. Tupolev. Tupolev’s success, political skills, status and international renown had proved insufficient to protect him from Stalin’s paranoia, and in October 1937 he had been arrested on a flimsy pretext. By 1939 he was leading a team of imprisoned engineers in “Special Technical Office 103”, part of a design bureau controlled by the NKVD. Initially it was tasked with developing a four-engined high-altitude bomber, known as project 57, and it appears to have been Tupolev’s initiative and persistence to substitute a simpler twin-engined tactical aircraft, project 58. The first prototype of this, Samolyet 103, flew on 29 January 1941. Designed with maximal attention to streamlining of the fuselage and engine nacelles, the 103 was optimised for speed, with simple dorsal and ventral positions for defensive guns, and an internal bomb bay for up to two ton of bombs. Reportedly Tupolev carefully considered the ergonomics of the crew positions, which suggests that he was sensitive to the criticism that the same had attracted on the SB, but test pilots would later complain the view for the pilot and navigator was poor. The 103 demonstrated a level speed of 643 km/h, which was very fast for the time. The second prototype, known as the 103U or project 59 aircraft, was enlarged to accommodate a fourth crew member.

In a pattern now familiar for Soviet bombers, development would be delayed by engine problems. The first prototype had Mikulin AM-37 liquid-cooled engines, and the powers that be envisaged turbosupercharged Klimov M-120 engines for the second and third prototype, evidently still aiming for high-altitude performance. But the M-120 was never produced in series and the AM-37 was soon abandoned. This forced a change to Shvetsov M-82 radial engines, which were about equivalent in power, but rated for lower altitudes. Reworking a large number of drawings was additionally disrupted by the need to evacuate the design bureau to the east, to Omsk in Siberia, and to a factory that had yet to be built! But this relocation also illustrates the fundamental strategic asymmetry that limited German options: Omsk is about 4000 km from Berlin, and it was safely out of reach of German bombers.

The new 103V prototype flew on 15 December 1941. Fitted with two M-82 engines in streamlined cowlings turning three-bladed propellers. It was capable of 521 km/h at 3200 m, a much lower absolute top speed than the earlier prototypes, although its performance at low altitude was still good. The 103V was followed by the 103VS, which was brought to the expected standard of series (S for Seryny) production with simplifications in equipment, improved armament, modified landing gear, and enlarged tail fins to solve a directional stability issue. The engine was the 1600hp M-82A. The first sample aircraft to this standard appeared at the front in April 1942.

With its designer rehabilitated, aircraft 103 became the Tupolev Tu-2, and the series production standard became the Tu-2S. Dive brakes, still fitted to pre-production aircraft, were omitted. The engines were standardised on the M-82FN with improved supercharging and direct fuel injection, which entered production in January 1943. In this form the Tu-2S was a very capable bomber, sleek, fast, and carrying a substantial war load. Defensive armament was limited, with the 12.7-mm UBT becoming standard fit in two dorsal positions and one ventral gun, while 20-mm ShVAK cannon were installed fixed in the wing roots. Compared with the Pe-2, the Tu-2S had the advantage that it was capable of carrying larger bombs.

However, the war situation was such that the type wasn’t ordered in large numbers. Factory 166 in Omsk delivered only 80 to combat units before, at the end of 1942, it was converted to produce fighters. Refusing to give up, the design team used the hiatus to refine the design of the Tu-2S, simplifying structure and reducing weight. Only in June 1943, after victories had secured the Soviet position, production was ordered to be restarted. Factory 23 at Fili near Moscow built 16 in 1943, 378 in 1944, and 742 in 1945. It was not a large plant by Soviet standards, and the older Pe-2 remained the most common Soviet tactical bomber. But as soon as the Tu-2S was available in substantial numbers, the VVS started to use it in massed, escorted daylight raids, striking targets in Division strength (nominally 93 aircraft) at a range of up to 500 km from their bases.

Production of the Tu-2S continued after the war, when Factory 166 returned to built the type and another production line was started at Factory 39 in Irkutsk. This brought the total production run to 2,527, of which 1,013 were completed during wartime: A relatively modest number by any wartime standard. But the Tu-2 was to see service well into the 1950s and was exported to a number of Soviet allies. Post-war versions included the Tu-2T torpedo bomber and the Tu-6 reconnaissance aircraft. Development also continued with a multitude of improved prototypes, a program that even evolved into a handful of Tu-12 jet bombers, but ultimately all of these were dead ends. The Tu-2S was the ultimate Soviet medium bomber with reciprocating engines, and the future belonged to purpose-designed jet aircraft.

It is instructive to compare the Tu-2 with two near-contemporaries that entered service in the last years of WWII, the Junkers Ju 188 and Douglas A-26 Invader. The Tu-2S was smaller than both, and about 25% lighter. Predictably, it was a bit faster than the Ju 188E-1 with engines of similar power, though the more powerful and technologically advanced American bomber outperformed it. It was credited with being able to carry a similar bomb load despite its smaller size, though in practice it often carried less. Its range was also shorter, though the number given is maximum range at economic cruising speed. Operational range for all types depended on mission profile and was far less than maximum range.

Table: Performance comparison of the Tu-2S, Ju 188E-1 and Douglas A-26B.

| Tupolev Tu-2S series 10 | Junkers Ju 188E-1 | Douglas A-26B | |

| Engines | 1850 hp Shvetsov M-82FN | 1740 hp BMW 801G-2 | 2000 hp R-2800-27 |

| Wing Span (m) | 18.86 | 22.00 | 21.34 |

| Length (m) | 13.80 | 14.96 | 15.24 |

| Empty Weight (kg) | 7,474 | 9,900 | 10,145 |

| Loaded Weight (kg) | 10,380 | 14,500 | 12,519 |

| Max Speed (km/h) | 547 km/h at 5400 m 482 km/h at sea level | 494 km/h at 6000 m | 578 km/h at 4480 m 546 km/h at sea level |

| Range (km) | 2,100 | 2,400 | 2,600 |

| Normal Bomb Load (kg) | 1,500 | 1,400 | 1,800 |

| Maximum Bomb Load (kg) | 3,000 | 3,000 | 2,700 |

The Soviet air forces during WWII are interesting because they had to focus on the essentials for survival – later on with the relative luxury, of course, of being able to fill the most painful gaps in its arsenal with aircraft supplied by its allies. The USSR built huge numbers of tactical low-altitude fighters, ground attack aircraft, and light bombers. It made a modest investment in medium bombers, primarily to have some long-range strike capability. It de-prioritised the equipment for a strategic air war, including heavy bombers, high-altitude fighters, twin-engined fighters, and nightfighters. Thus its priorities were starkly different from those of the American and British forces.

Admittedly, it was in part able to do so because the Luftwaffe didn’t have the means for a strategic air war against the USSR. The USSR was able to quickly relocate major factories to Siberian cities that were out of realistic reach for any WWII bomber, so there is little point in criticising the Luftwaffe for not attacking them. In contrast, Germany did not have the option to move factories out of range, as it was simply too small for that, but in 1941-1942 it conquered so much territory that it effectively denied the USSR the bases for a strategic offensive until later in the war. Hence neither side had much to gain by a strategic air campaign. The air war at the Eastern Front remained tactical, not only by choice, but also by necessity.

Next: Chapter X