The Early War Years

Luftwaffe

The Military Aviation History channel on YouTube has started a series on Luftwaffe doctrine, bombers and bombing: The first episode discusses the priority the Luftwaffe gave to bombers. This is well documented and promises to be a good series!

It has become traditional to see the death of Lieutenant-General Walther Wever, in an air accident in June 1936, as a turning point in the history of the German Luftwaffe. Wever, so goes the story, was the main proponent of heavy long-range bombers in the Luftwaffe, and the decision after his death (some time later, in April 1937) to abandon these aircraft in favour of smaller bombers and dive bombers was a fatal strategic mistake that doomed Germany to defeat. But that version of events reflects the prejudices of Allied strategists far more than the reality of the German position. For a start, it is wrong to infer from the cancellation of the Dornier Do 19 and Junkers Ju 89 that the Luftwaffe entirely abandoned the idea of acquiring long-range bombers, as a few weeks later Heinkel received a contract for what would become the He 177. That was to be an unlucky aircraft, but its specification in significant ways paralleled the British specification P.13/36, which would lead to the Lancaster and Halifax.

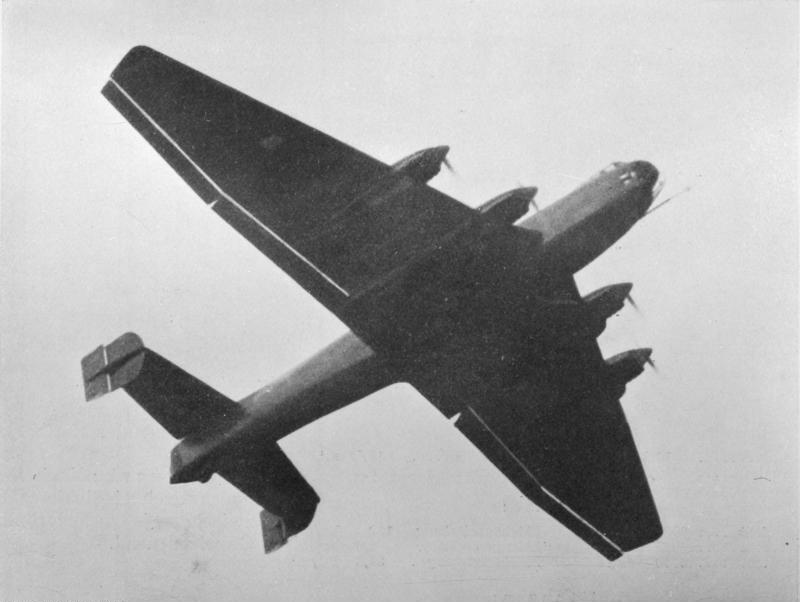

It is true that Wever had supported the development of two large four-engined bombers, built to a specification issued in the summer of 1935. But it is also important to consider that these prototypes were not all that impressive, and Wever had agreed in May 1936 to give them a lower priority than the fast medium bomber program.

This initial project is often referred to as the “Ural Bomber” program, an evocative name that suggests the ability to cover the entirety of Europe and brings to mind the evacuation of Soviet industrial plants to the Ural Mountains and beyond in 1941. (A situation that was foreseen by Wever.) But the Ural is about 3000 km east of Berlin. The Dornier Do 19 and Junkers Ju 89 had a maximum range of 2000 km, not even enough for a round-trip to the Ural Mountains starting from Moscow! With the intended bomb load of 1600 kg their range was cut to 1600 km. From bases in Germany, that wasn’t even enough to fully cover Britain or France. It was about equivalent to the range performance of the British Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, an older twin-engined heavy bomber, and inferior to the Short Stirling, which admittedly entered service later, in 1940: With 3500 lb (1590 kg) of bombs, the Stirling had a range of 2010 miles (3235 km). It was logical that even before the Do 19 and Ju 89 made their first flights, the German air force realised that they did not meet its operational needs, and drafted a new “Bomber A” specification demanding a maximum range of 5000 km. At the time the RAF was designing its heavy bombers for a maximum range of 3000 miles (4830 km).

When they made their first flights in 1936 and 1937, the Do 19 and Ju 89 were impressive, but obsolescent technology. Both were underpowered, the Ju 89 by four 960 hp DB600 in-line inverted V-12 engines, the Do 19 by four radials, on the first prototype the 715 hp Bramo 322H-2, but intended to be replaced by the BMW 132F. The unarmed Ju 89V1 had a top speed of 389 km/h, the projected speed of a putative Do 19A production aircraft (with reduced defensive armament) was 370 km/h. Both bombers had been designed to have 20-mm MG-FF cannon in hydraulically powered dorsal and ventral turrets, an advanced feature that turned out to be impracticably heavy, as these turret designs required two men to operate them (presumably a gunner and a loader, as the MG FF was fed with drums). The Luftwaffe rightly considered that the Do 19 and Ju 89 might be useful as transport aircraft. The Ju 89, a much heavier aircraft than the Do 19, did have an impressive potential to carry large and heavy loads, which inspired the derivation of the Ju 90 airlines. Continued development would by 1942 result in the very useful Ju 290 long-range reconnaissance aircraft. But this process involved step-wise replacement of the fuselage, engines, wing, and landing gear, so that the Ju 290 did not have much in common with the Ju 89.

American and British critics of Luftwaffe policy with hindsight saw the decision to cancel the “Ural bomber” as a shift towards a tactical role for the Luftwaffe, and away from a strategic role. RAF and USAAF theorists saw the strategic role as the only proper role for an independent air force, the role in which it could make its own independent contribution to victory. But unlike the Germans, they did not have a land border with the enemy to worry about. The Luftwaffe could hardly avoid giving direct and indirect support to the Army, certainly not after combat experience in Spain had demonstrated the value of this. Prior to the war, it managed to develop a valid and effective doctrine for the operational use of air power, independent but in partnership with the army, striking not only at targets on the battlefield but primarily at the enemy air force and logistical targets behind the front line.

That did not imply a total neglect of a strategic role, but it was impossible for the Luftwaffe to invest in heavy bombers on the massive scale that the RAF and USAAF would. Also, in the perspective of Berlin the strategic priorities were different. Britain, the USA, and the USSR were potential enemies with the ability to (de)localise their industrial effort well out of range of any extant bomber. In so far as Germany had any strategic hope of winning a world war, it was to win the Battle of the Atlantic — shipping, not industry, was their enemy’s key vulnerability. After the Battle of Britain, ports were indicated as the priority target for German bombers. And a demand for long-range combat aircraft emerged with a focus on naval roles. This made strategic sense, but the poor cooperation between Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine negated many of the gains that might have been obtained. Incidentally, the RAF has also been fairly criticised for allocating long-range aircraft to Bomber Command at times when they would have made a more useful contribution to Coastal Command.

From the perspective of the RLM, Germany’s rapidly expanding aircraft industry had enough difficulty producing a sufficient number of smaller aircraft, and the production of a small number of heavy bombers of dubious operational usefulness was not desirable. Machine tools, raw materials, and fuel were already scarce. It is implausible that the Do 19 or Ju 89, if they had been put in production, would have made a significant difference in the battle of Britain. Perhaps they could have been developed to carry more bombs farther than the medium bombers (on paper the Ju 88 had at least equivalent payload-range performance) but the available escort fighters were short ranged. The decision to focus on the mass production of the available medium bomber designs in 1937 was probably the technically correct one, as several modern designs with good performance were available.

Misfire

The least successful of these designs was the Junkers Ju 86. This type had made its first flight in January 1935, but bomber production was ended in 1938 and the type was phased out from combat duties. The Ju 86 had been designed to have dual civilian and military roles, as outlined in a specification issued in 1933. Unlike its contemporaries, it was large enough to be a useful airliner in civil guise, carrying ten passengers in reasonable comfort, and even enjoyed modest export success as such. The bomber version had defensive gunnery positions in the nose, an open dorsal position, and a ventral “dustbin” turret. It could carry 1000 kg of bombs internally. In combat in Spain the innovative Jumo 205D Diesel engines of the Ju 86D proved a liability, as they were unreliable and responded poorly to the stresses of combat use.

The Ju 86E adopted the BMW 132F radial, and was available for export as the Ju 86K. Sweden built the type as the B3 bomber with Bristol Mercury engines. But even the Ju 86E was clearly outperformed by later types, and the last would be retired from bomber units after the brief campaign in Poland. The Ju 86 survived in Luftwaffe service in a handful of specialised high-altitude reconnaissance versions with Jumo 207 engines, increased wing span, and pressurised cabins, the Ju 86P of 1940 and the Ju 86R of 1943. No doubt these were useful but nevertheless their continued production alongside the superior Ju 88 seems a mistake.

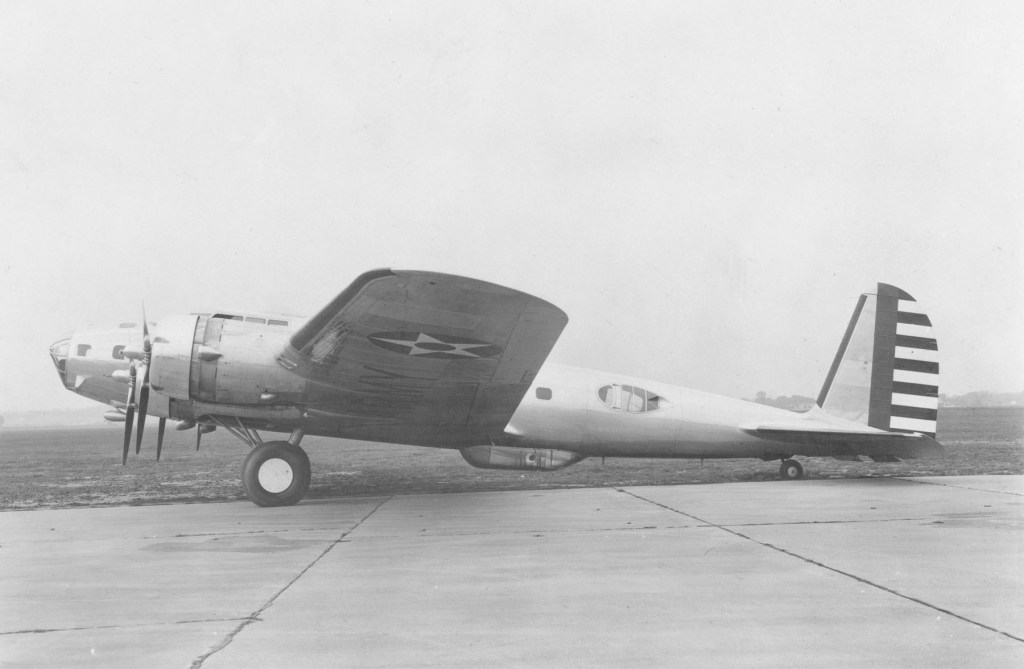

The Three

The direct competitor of the Ju 86 was the Heinkel He 111 and this design would have a long career, by some standards an excessively long one. As it made its first flight in February 1935, the He 111V1 prototype was a beautiful aircraft, with elliptical wings and tail surfaces and a streamlined fuselage. In this initial version, it had a conventional, well-streamlined nose with a stepped cockpit above and behind it for the flight crew. It was unpractical and uneconomical as a commercial transport and would be operated only in limited numbers by DHL. The initial He 111A-0 bomber as evaluated in 1936 was also unsuitable as a bomber, because with BLW VI 6,0Z liquid-cooled engines it was underpowered and sluggish when fully loaded. However, the BMW VI was regarded as little more than an interim engine, and a version powered by the new Daimler-Benz DB600 engine was already being tested. This He 111B entered service in late 1936. It was armed with the traditional three rifle-calibre machine guns (7.9mm MG15) in nose, dorsal, and ventral positions. It carried its bombs in vertical cells in the internal bay between the wings, from which they were released with a characteristic rotating drop, familiar from wartime footage as this feature was retained by all later He 111s. The He 111B-2 was the first major production version, with 950 hp DB 600CG engines. But the Daimler-Benz inverted V-12 was much in demand for fighter applications. Consequently, the Luftwaffe did not accept the He 111D with 1050 hp DB600Ga engines in a much improved, more streamlined installation. Instead, from January 1938 production switched to the He 111E with 1075 hp Jumo 211A-1 engines. Although technologically advanced, the Jumo 211 would become a “bomber engine” while the DB600 and DB601 were prioritised for fighter applications.

The He 111B was very quickly sent to fight in the Spanish Civil War, where the Ju 52/3m had clearly shown its limitations as a bomber, followed by the He 111E as soon as these became available. In various deliveries a total of 95 Heinkel He 111s would be sent, of which 58 would survive the war to be handed over to the new Spanish air force. They quickly proved to be the best of the German bombers in Spain, being superior to the Do 17 and Ju 86 and far superior to the Ju 52/3m. The He 111 had a good performance, had fine handling characteristics and carried a decent bomb load. Despite its speed it was vulnerable to interception by modern fighters, in particular the I-16, but combat losses were still relatively light.

Meanwhile, the wing of the He 111 had been redesigned to simplify production, abandoning the elliptical contours in favour of straight leading and trailing edges, with rounded wing tips. This resulted in the production of the He 111F, with Jumo 211 engines, and the He 111J, its equivalent with DB 600 engines, as the supply situation of the latter had improved. The F and J were to prove interim models as another major redesign was in the works, in the form of a new, fully glazed, and somewhat asymmetrical, nose. The pilot moved from a traditional stepped cockpit to the left seat position in the nose, with the gunner and bomb aimer to his right. The gun mount in the tip of the nose was offset to the right, resulting in an asymmetric contour. The ventral “dustbin” turret was replaced by a permanent ventral fairing, and the dorsal gunnery position was redesigned, but three 7.9 mm machine guns still constituted the whole of its defensive armament. In this form, the He 111 now looked as it is most familiar from WWII pictures. With 1175 hp DB 601Aa engines this He 111P-1 had a maximum speed of 400 km/h, though this decreased to 325km/h with a maximum load. It could carry 2000 kg of bombs.

The new cockpit design fell in with the trend of Luftwaffe bombers. Bulbous cockpits with extensive glazing, usually a large number of small panels, and often without a “step” for the pilot’s windscreen, appeared not only on the He 111 but also on the Do 17, Ju 88, Ju 188, He 177, and even the reconnaissance models of the Ju 86. They put several crew members in close proximity in the nose of the aircraft and provided a good all-around view. This strongly contrasted with the RAF design philosophy of designing bombers with a nose gun turret, which necessarily put the cockpit farther back. The German preference thus emphasised ergonomics over defensive firepower.

Initially, the Luftwaffe initiated parallel production of the He 111P with DB 601 engines and the He 111H with Jumo 211 engines. First the He 111P entered service in the spring of 1939, with the He 111H following a little later. The production rate was quite high, as three factories were building the He 111P and three more the He 111H, with the latter being built at a rate of about 100 per month! Older He 111 models were quickly replaced and the Luftwaffe entered the war with 389 P-series aircraft and 400 H-series, as well as a small number of older models to make a total of 808 He 111 bombers. From early on in 1940 only the He 111H would be built, as there was a more plentiful supply of the Jumo 211, and standardisation had its advantages.

But despite the substantial design modernisation that the He 111H and P series represented, the He 111 was fundamentally an older bomber design. Its performance was no longer fully adequate and its defensive armament was weak. The He 111P-4 and H-2 had an additional gun in the nose plus two more firing through side windows, with an increase of the crew from three to five, but this was still an inadequate defence. The H-3 introduced an MG FF cannon in the front of the ventral gondola. The opposition encountered over Poland and France was largely ineffective, but the losses over Britain were high. The He 111 was in fact being gradually phased out in favour of the faster, superior Ju 88, for which the Reich had adopted mass production methods, while the Luftwaffe also looked forward to receiving the Ju 288 and He 177. If production had been 1399 aircraft in 1939, it decreased to 827 in 1940 and 930 in 1941. By August 1941, attrition had reduced the total frontline strength to 190.

Here, however, the true weakness of Germany’s bomber policy came to the front. As we will see, it proved largely unable to introduce newer bombers in service, with the “Bomber A” and “Bomber B” projects ending in failure. Consequently the He 111 remained in production until late 1944, well beyond the initial plan of phasing out production in early 1942. Instead production increased again to 1337 in 1942 and 1408 in 1943. It was fundamentally a good aircraft with excellent flying characteristics, it was easy to produce and maintain, and it was well-liked and versatile. The He 111H-6 with Jumo 211F-1 engines and broad-bladed propellers became a major production model, as was the H-16 with Jumo 211F-2 engines and various improvements. Defensive armament was somewhat reinforced by moving the MG FF into the fuselage nose, and replacing the MG15 with the newer MG81 or the 13mm MG131. Some late production aircraft had a small electrically powered dorsal turret with a single MG131. But the He 111 was increasingly seen in supporting roles: As a transport, as a carrier for guided missiles or even an air-launched V-1, as a paratroop aircraft, a glider tug, or a sweeper of magnetic mines. A proliferation of subtypes had various defensive armament improvements or special mission equipment. If nothing else, the He 111H proved adaptable. Because the Jumo 211 was being phased out of production, the He 111H-21 of early 1944 was fitted with the 1750hp Jumo 213E-1, and the final version was the He 111H-23 with Jumo 213A-1 engines. The 714 aircraft built in 1944 ended a production run of over 7000 He 111s, the majority of which had been built after the type became obsolescent. The He 111 story did not even finish at the end of WWII, as the type was also built in Spain and remained in service there into the 1960s!

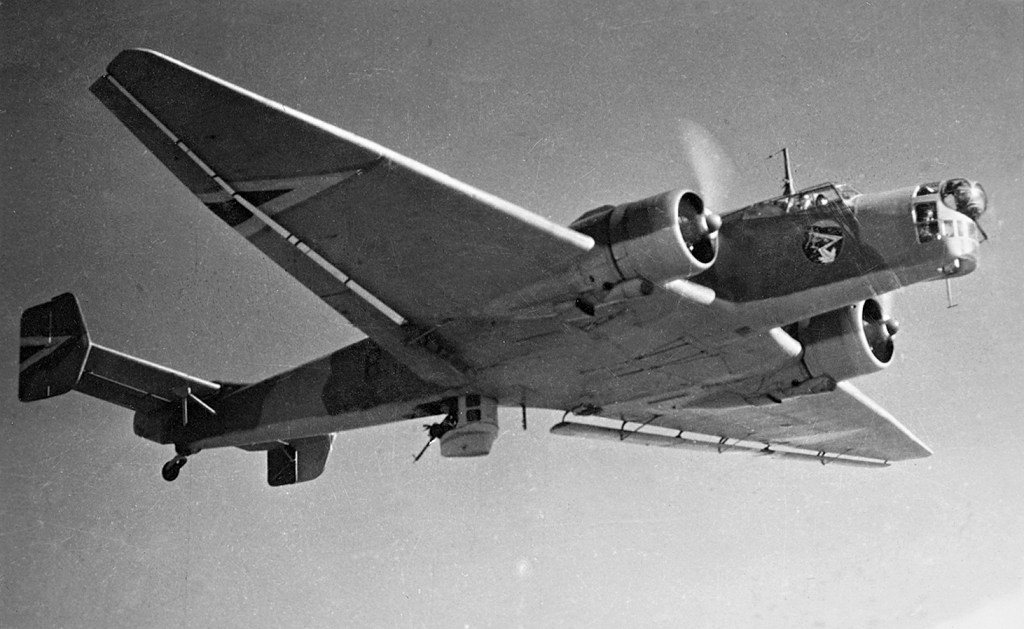

Another major Luftwaffe bomber in 1939 was the Dornier Do 17. The origins of the Do 17 are somewhat murky, because the regime chose to pretend, for political reasons, that it was was designed as an airliner; in fact it didn’t even remotely have any usefulness in that role. The first Do 17V1 prototype, as it flew on 23 November 1934, was a remarkably sleek aircraft, with a slim pencil-like fuselage and a long tapering nose. This aircraft had a single tail fin, but the second prototype introduced twin tail fins. A series of eleven prototypes was ordered helped to gradually refine the Do 17 into a fast bomber and reconnaissance aircraft with a shorter but still streamlined “glass nose”, and alternative in-line or radial engines.

A confusing array of versions was produced. The Do 17E bomber and the Do 17F reconnaissance aircraft were powered by BMW VI liquid-cooled V-12 engines, and built from 1936 onwards. The Do 17K of 1937 was built for export to Yugoslavia, with French Gnôme-Rhône 14K radials. The Do 17M bomber featured some redesign of wing and landing gear, and Bramo 323 radials. The Do 17P was a reconnaissance model with BMW 132N engines that replaced the Do 17F. The four Do 17Rs aircraft were specialised photo-reconnaissance derivatives of the Do 17M with DB 601A engines, and the three Do 17S were similar adaptations of the Do 17Z. A new nose was designed for the Do 17U, and became standard on the Do 17Z. The looks of the type changed significantly with this shorter, deeper nose which had a characteristic ‘bug eye’ panelling of the nose tip and a position for an additional gun to cover the lower rear.

The Do 17Z-1 with Bramo 323A-1 engines and the Do 17Z-2 with 323P engines were the major wartime production versions, accounting for 422 aircraft by 11 May 1940, at the start of the battle for France and the Low Countries. Dornier and its subcontractors would complete 913 Do 17Z models. The Do 17Z-2 was an effective bomber in 1939-1941 and was generally appreciated as a rugged and reliable aircraft. Its defensive armament was increased to six MG 15 machine guns firing from within its compact crew compartment, one in the nose, one in the windscreen, one in the ventral position, one in the dorsal position, and two firing to the beam, but this somewhat improvised setup was still inadequate. Their performance was such that two nightfighter models were developed from this series, the Z-9 and Z-10, but these were not altogether successful. The designation Do 215B was given to a development of the Do 17 with the more powerful Daimler Benz DB601 engine, originally intended for export, but absorbed in Luftwaffe service. Again, this type was used both in reconnaissance and bomber roles.

The Do 17 had been designed as a fast bomber, and in Spain the F and P models were capable of outrunning the opposition. But at the start of WW2 the improved performance of enemy fighters increased the Do 17’s and Do 215’s vulnerability. The type was also small, with poor defensive armament, a limited bomb load, and little development potential. If the He 111 could be said to roughly the Luftwaffe’s equivalent of the Vickers Wellington, then the Do 17 was more its equivalent of the Bristol Blenheim. Production of the Do 17 was ended in July 1940 and that of the Do 215 in January 1941. Well before the war, Dornier had started work on a successor, the Do 217, which despite its designation was not a development of the Do 17, but a bigger, stronger and heavier aircraft. The Do 217V1 made its first flight in October 1938. Thus the approaching obsolescence of the Do 17 turned out to be something of a blessing for Dornier and for the Luftwaffe, which would in due course receive a more modern bomber.

The third major bomber type in service at the outbreak of the war was the Junkers Ju 88, and this managed to be both a success and a disappointment to the Luftwaffe. A success, because it was an excellent and versatile aircraft. A disappointment, because the high hopes of mass-producing it on assembly lines were not realised and the Ju 88 was available both much later and in smaller numbers than required, which caused serious friction within the German military-industrial complex. So high were the hopes that in May 1938, in a time of increasing international tension, Göring had ordered the production of 7000 Ju 88 bombers, which were intended to become the mainstay of the future Lufwaffe, displacing the other medium bombers. At Junkers, Dr. Heinrich Koppenberg promised that a consortium of manufacturers organised around Junkers would produce 250 per month and held out hopes for 300. In July 1939 the Luftwaffe was forced to reduce the scale of its re-armament plans, but the Ju 88 was explicitly exempt from these cuts, which hit all other aircraft types with a reduction of 20%. It was decided that production of other aircraft, such as the Ju 87, would be scaled back to mass-produce the Ju 88. In October, Koppenberg was even given the authority to requisition the plant of other manufacturers in support of the Ju 88 program! This was to be one of the top priorities for the German industry. High expectations resulted in a serious crisis of confidence when they could not be realised. Organising the collaboration between the factories participating in the program needed to overcome initial hurdles, the Ju 88 suffered from the predictable teething troubles, and a stream of modifications interfered with mass production. The Ju 88 entered service a year later than expected and its initial production rate was very low. By the end of 1939 only 69 had been delivered, although the Luftwaffe would receive 3,962 Ju 88A bombers in 1940 and 1941. The production of all models of Ju 88 would climb to over 15,000 before the end of WW2, of which over 9,000 were bombers. Despite these impressive numbers, there were never enough Ju 88s to replace the older bombers entirely.

The Ju 88 was a younger design than the Ju 86, Do 17 and He 111, and never pretended to be an airliner, because its specification was contemporaneous with Hitler’s announcement in 1935 of the new German air force. That specification was for a fast medium bomber, a Schnellbomber with minimal defensive armament (a single machine gun) but a top speed of 480 to 500 km/h. With an eye on mass production, the aircraft had to be produced in 30,000 man-hours or less. Junkers had offered two designs, the Ju 85 with twin tail fins and the Ju 88 with a single tail fin. The legacy of past Junkers designs, which tended to be angular in shape and made use of corrugated skins, was replaced by a clean streamlined shape and a smooth stressed-skin structure. The Ju 88 was ordered and the first prototype, powered by DB600 engines, made it first flight in December 1936. The third prototype had the intended Jumo 211A engines and reached a top speed of 515 km/h.

It is tempting to speculate what would have happened if the Luftwaffe had stuck with the Schnellbomber concept. Historically, the Ju 88 was the closest Lufwaffe equivalent to the British De Havilland Mosquito, which was designed as an unarmed fast bomber and adhered to that concept. (Incidentally, both the Ju 88 and the Mosquito proved to be useful heavy fighters and nightfighters.) The development of the Ju 88 diverged on a different track early on, as the fourth prototype was reworked to provide a dive-bombing capability, which required structural strengthening and dive brakes. As it entered service in 1939, the Ju 88A also sacrificed some streamlining to be fitted with the typical German bomber cockpit of the time, including a transparent nose composed from numerous flat panels, and a ventral gondola to help defend the lower rear. With two 1200 hp Jumo 211B liquid-cooled V-12s, installed in neat cowlings fronted by circular radiators, a bomb-laden Ju 88A-1 could fly at 426 km/h. That was a creditable speed, but well down from the speeds achieved by the prototypes (the V-5 had set a record of 517 km/h over 1000 km with a 2000 kg load) and not fast enough to avoid interception by enemy fighters. With 1400 hp Jumo 211J engines and longer span wings, the A-4 of early 1941 was faster, but a speed of 470 km/h merely made interception by enemy fighters difficult, it did not make it impossible. And while up to 1400 kg of bombs could be carried in two internal bomb bays, this was achieved with small bombs of 50 kg. The Ju 88A had to carry heavier loads externally, on four ETC 500 pylons under the inner and two ETC 250 under the outer wings, at the cost of additional drag. Optionally some versions could carry ETC 1000 racks. Later a bulged wooden bomb bay was developed for larger internal loads, up to 3000 kg, but this was not much used.

With hindsight, some of the performance sacrifices made in the A-4 seem barely justified. Thanks to its good handling and automated dive bombing controls, the Ju 88A was not a bad dive bomber, but this capability was still secondary, primarily useful against ships. As for the additional defensive armament, it remained relatively weak. Throughout its long career, the Ju 88 would never have the powered operated turrets of the British mediums. The most characteristic armament features of various models were one or two rotating armoured glass disks installed at the rear of the cockpit, fitted with machine guns such as the MG 15, MG 81Z, or MG 131. A machine gun was installed in the windscreen to provide a frontal defence, and the ventral gondola typically had one or two machine guns at the rear. Various armament increases became optional during the Ju 88As long production run, such as MG FF cannon installed the nose or in the front of the ventral gondola, and additional machine guns in the nose or the sides of the cockpit. As many of these options could be implemented as field modifications, the number of variations was high. But the effectiveness of additional guns was limited as the bomber only had a crew of four, the cockpit was rather cramped, and the guns were manually aimed.

In late 1943 the Ju 88 would return to the concept of a fast bomber with minimal defensive armament, in the form of the Ju 88S, which had an aerodynamically cleaned up nose, a crew of three, and retained only a single MG 131 to defend the rear. The Ju 88S was also equipped with more powerful BMW 801 or Jumo 213 engines. The Ju 88S-1 was built as a conversion of existing A-4 airframes and with 1730hp BMW 801G engines reached 603 km/h at 8000m. But internal bomb load was reduced to 900 kg, and the S series aircraft would find their best use as “pathfinders” marking targets for other German bombers.

A more practical approach towards improving both the Ju 88’s performance and its defensive armament was represented by the Ju 88B, of which a prototype flew in June 1940. Its new nose was deeper, but more rounded, with smooth contours instead of the “bug-eye” panelling of the Ju 88A. Redesigned nose, dorsal and ventral installations were fitted with the MG 81Z, and the installation of a small DL131 turret on top of the cockpit, with a single MG 131 machine gun, was considered. The Ju 88B , especially in combination with Jumo 213 or BMW 801 engines, offered a handsome performance improvement over the Ju 88A. But despite production plans being made in late 1940 they never moved beyond the prototype stage, and a mere handful of these fast machines were used for reconnaissance purposes. Instead the new features would be incorporated in the Ju 188.

Thus the Luftwaffe could be accused of wasting some of the potential of its best bomber, even if the Ju 88A was a good bomber and served successfully on all fronts. The Ju 88 airframe would also prove its versatility in the D series reconnaissance aircraft, the C series heavy fighter, and the G and R series nightfighters. The Ju 88P anti-tank aircraft was undoubtedly a waste of time.

The Battle and the Blitz

In September 1939 what was intended to be a localised conflict exploded in a new world war. Considering that WWI had been initiated in much the same way, the leadership of Nazi Germany might have been better prepared for a large conflict than it was. Lack of preparation also affected the Luftwaffe’s bomber force, which had shortages of trained aircrew. A Chief of Training had been appointed in February 1939 to oversee aircrew training, but was denied his request for additional training aircraft, because the priority was given to equipping new frontline units. The use of the Ju 52 as multi-engine trainer would become a vulnerability because of the strong tendency to requisition these for transport and airborne assault duties. The Luftwaffe was even short of bombs. Insufficient ammunition stockpiles were a general concern in the armed forces.

In October 1938 Göring had announced plans to bring the size of the Luftwaffe to 21,750 aircraft, a five-fold increase, to be achieved by 1942. Even if the decision to bring the German economy on a war footing had already been made, as it appears it was, this was a goal well beyond Germany’s financial and industrial means. Nor did it have access to the fuel for such a force. It is possible that the announcement was primarily intended to overawe the French and British. In any case, a few months later, the Reich found itself in a financial meltdown following on the Munich crisis. Germany was forced to made deep cuts in the allocation of steel to its armed forces, and in the spring of 1939 the production of ammunition was cut back sharply, more so than the production of aircraft. The outbreak of war inevitably triggered a rapid switch from the productions of weapons to that of ammunition, as its industry was incapable of meeting the demand for both. The grandiose ambitions of the Nazi regime collided with the stark reality that supplies of steel, aluminium, copper, fuel and other essentials were inadequate.

Germany therefore was not in the position to plan a strategic bomber offensive. The RAF, relatively safe on an island with the prospect of using all the resources of a large world empire and the growing contribution of the American industry, could contemplate the long-term effects of laying waste to the economy and industry of its opponent. The practical reality for the Luftwaffe was that if the war became so long that bombing the enemy industry made a significant difference, Germany would almost certainly lose it. The more logical targets for the German bombers had an immediate tactical or operational value: Enemy warships and freighters at sea; airfields and command and control centres; railway yards, bridges, ports, and supply depots; troop concentrations at or behind the front lines.

Thus in the initial attack on Poland, many German bombers targeted airfields, bombing about thirty of them on the first day of war, but achieving incomplete success because Polish aircraft had been moved to dispersed fields prior to the attack. As the German forces on the ground quickly advanced, the retreating Polish forces on the roads were highly vulnerable to bombing and strafing, which accidentally or intentionally also hit columns of civilian refugees. However, from the start an aerial assault on Warsaw was part of the plan, and as German forces surrounded the capital city, the bombing became intense. As a defended city, Warsaw was in principle a legitimate target, and at least some of the attacks targeted military infrastructure. But it is clear that the Luftwaffe also bombed to terrorise the civilian population. The heaviest raid, on 25 September, dropped 560 tonnes of high-explosive bombs and 72 tonnes of incendiary bombs on the city centre. The scale of the destruction was gleefully published by German propaganda, in an obvious attempt to intimidate.

On the Western front, some of the Luftwaffe’s first operations targeted British warships at sea, and the important fleet ports of Rosyth in the Firth of Forth, and Scapa Flow in the Orkneys. The damage done was limited, but served to show that the reach of the German bombers extended to the far north of the British isles. Ships and ports were also the key targets during the brief Norwegian campaign. Following the German offensive against France, Belgium and the Netherlands of May 1940, targets were again primarily tactical and operational, with the notable exception of the heavy bombardment of Rotterdam. The threat of such a bombardment was sufficient to induce the Dutch defenders to surrender, but due to communication failures the city was nevertheless heavily hit. Another city-sized target presented itself as the British and French forces in the North withdrew to Dunkirk to be evacuated overseas, though in this case again many attacks targeted the ships and the port facilities.

For this type of campaign, the medium bomber force was well suited. It demonstrated its flexibility and responsiveness to the evolving situation on the ground. Neither Poland nor France had an effective air defence control system, which meant that any fighter opposition tended to be uncoordinated and small in number. RAF Hurricanes sent to fight in France operated under the same disadvantage. The German bomb loads were adequate for the targets and because the Kampfgruppe could avail themselves of captured airfields to base their aircraft closer to the front or stage attacks through them, missions could be short and numerous. Under such conditions, the Luftwaffe made a strong contribution to the German success, at the cost of significant but manageable attrition. It had lost 1909 aircraft to all causes (including a large number of accidents), and 974 aircrew. Aircrew held in captivity in France were freed to return to the service.

But as planning for an air offensive against Britain began, several of the commanding officers were aware that the available force was inadequate for the task, whatever that was. It might be to gain air superiority over southern England to enable an invasion across the channel, but the plans for operation Seelöwe were hardly realistic in face of the vast superiority of the Royal Navy. As the Battle of Britain was fought, British destroyers would continue to operate in the channel and shell the launching ports for an invasion, while a large naval force was concentrated in Rosyth for anti-invasion duties. Even if a first wave achieved a landing on the British coast, the near-impossibility of following up with reinforcements or supplies made it a forlorn hope. A more realistic prospect was to force the British government to the negotiating table by bombing, or to bring about a change of government in favour of those more favourable to reach accommodation with Germany. But this clearly needed a large and sustained effort, and nobody really knew what the best target was, the war industry or the cities and civilian population, so the plans switched back and forth between these options.

However vaguely defined the goals were, in the late summer and autumn of 1940 the Luftwaffe embarked on something unique: A strategic air campaign with, ostensibly, a short-term goal. In particular, if its purpose was to prepare for an invasion, then victory needed to be achieved before winter. If the goal was to force the British government to the negotiation table then time still worked against the Germans, because Britain would recover from its moment of greatest weakness after Dunkirk, and because Hitler was already considering an attack on the USSR. Later Allied bombing offensives would have long-term goals, of undermining the enemy’s economy and industry, eroding his air force by attrition, destroying his will to fight, or even of keeping the morale of the home front up by retaliation. Embracing the long view would be a boon to future commanders, who could respond to adversity by pleading for a larger and sustained effort, with the obvious downside that it deprived them of an incentive to abandon bad ideas. By setting short term goals the German commanders boxed themselves in, and moreover gave the British the advantage of a strong defensive position that they only had to hold for a limited time to win the battle. In those circumstances it is not clear that any force could have obtained the desired result.

This being a pioneering effort in strategic bombardment also meant that the Luftwaffe piled on errors that their enemies would also make, but would have time to learn to avoid. Target intelligence was poor, resulting in attacks on the wrong airfields, and only partial targeting of the aviation industries in southern England. Damage assessment both overestimated the losses inflicted on the RAF and failed to identify successes worth following up. The British radar and command and control centres were not systematically targeted, a remarkable neglect given that the Germans themselves used an increasing number of radar stations to defend their own territory. The use of external tanks to increase the range of their fighters was another missed opportunity. Adopting flawed escort tactics that tied the fighters too close to the bombers was something worse, as fighter unit commanders knew well that it was a serious error.

Would a heavy long-range bomber have a made a major difference? Many authors have stated that it would have, especially in accounts written primarily from the British perspective, but without offering much in the way of evidence. In the autumn of 1938 a report by the German general Felmy had concluded that with the available medium bombers, a successful offensive could not be mounted from Germany, but needed airfields closer to Britain. In the summer of 1940 such bases became available, and Luftflotte 2 and 3 could base their 1,131 long-range bombers close enough to their targets to have most of Britain within reach. Their priority targets were in Southern England. Thus the range of the available bombers was adequate. The real problem for bombers operating out of Belgium and France was the range of their fighter escort, and having larger bombers would not have changed that.

To estimate the impact that a German four-engined heavy bomber would have had on the Battle of Britain, we need a plausible hypothesis of what it could have been. If in the summer of 1940 the Luftwaffe had in service a substantial number of aircraft equivalent to the Boeing B-17G or the Avro Lancaster, it might well have changed the course of the battle. But that is an anachronistic counterfactual. In August 1940 the Short Stirling was just reaching squadron service (it would fly its first operational missions in February) and the USAAC was starting the receive the first B-17Cs, which the RAF would find operationally unsuitable when it received them in July 1941. What might have been available to the Luftwaffe was a development of the Do 19 or Ju 89, with the latter the more plausible option as historically its development was continued.

One can imagine a Ju 89 development with increased range and payload, powered by four 1200 hp Jumo 211. In all likelihood it would have been defended only with rifle-calibre machine guns in manual mounts, which would have made it as vulnerable as the smaller bombers. (Remote-controlled turrets were planned for the He 177, but the first turrets were not delivered until February 1942.) Its operational speed then might have been around 350 km/h, considerably slower than a Stirling or than the medium bombers in service, making it relatively easy to intercept for a Hurricane (in contrast to the fast Ju 88A or Do 17Z). One can imagine that it would have been a rugged aircraft able to take a lot of punishment, which is significant as the RAF’s fighters mostly had only .303 machine guns, and even medium bombers often returned home despite numerous hits. The Ju 89 was initially designed for a modest 1600 kg, but presumably a design priority would have been to increase its bomb load to well above that of He 111 (2000 kg) or Ju 88A (1400 – 2000kg). However, even a Ju 290 had a capacity of only 3000 kg.

This would have given the Luftwaffe a force of at most a few hundred four-engined bombers, given the shortages of materials and the need for large numbers of tactical aircraft, even if we assume that the Luftwaffe would have been willing to trade medium for heavy bombers at a 2-to-1 ratio. (In reality it might have been worse.) Slower than the medium bombers, with insufficient defensive armament to survive in daylight without a strong fighter escort, these would not have added that much to the Luftwaffe’s capability to strike at point targets in southern England. It is even possible that by introducing a type that could not operate effectively in daylight, and flew at lower speeds, it would have weakened the overall force structure. The more logical choice would have been to use such a heavy bomber mainly or exclusively for it night bombing. With no need for long range, it could have been loaded to capacity, for attacking city targets with a mixture of high explosives and incendiaries. Much greater damage could have been done to London and other British cities. But it is unlikely that this would have have been decisive, given what we know of the effects of large-scale attacks on cities later in the war. It is certainly not evident that to the Luftwaffe, this would have been worth the expense and logistical headaches.

It appears a classical case of mirror imaging. During the Battle of Britain, the RAF decided that it would need four-engined heavy bombers to sustain its own offensive against Germany. This need was then reflected back on the enemy, ignoring the asymmetries of time, space, and purpose. That does not mean that the state of development of the German bombers was satisfactory to their owners. We will see later that it was anything but.